The Public Intellectual Paradox

A brief look at the tensions facing public intellectuals in the Information Age. Our subject: Yuval Noah Harari and his latest book, Nexus.

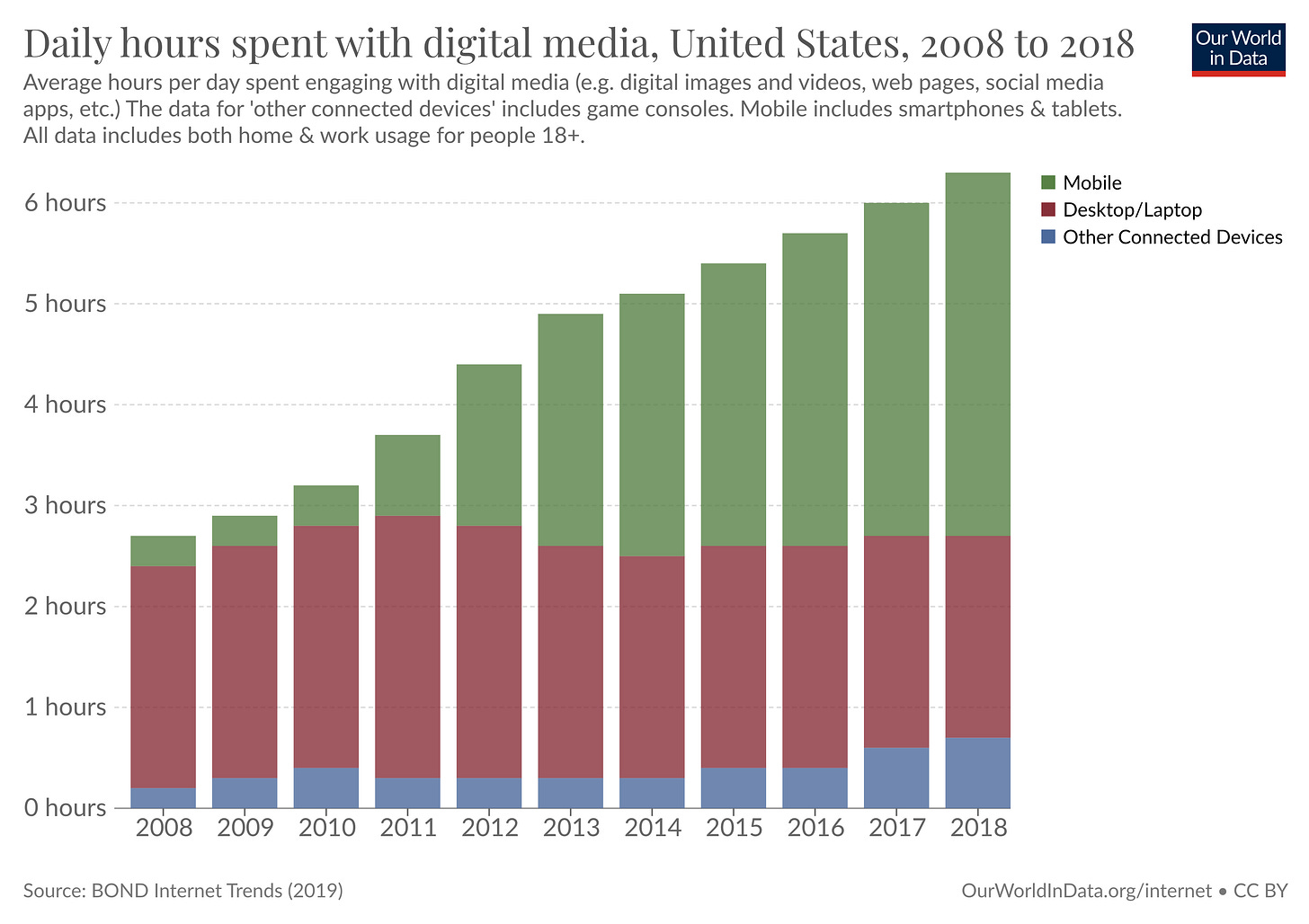

It is a Golden Age, it is a Dark Age: If one wanders over to a site like Our World in Data, it is easy to see how one can readily spin up narratives of miraculous prosperity or impending doom. We can look at the chart of trends in global GDP or global greenhouse gas emissions and respectively see riches or squalor over the horizon. The seeming conflict between any selection of data should increase our skepticism of simple narratives. In some ways, this process may already be underway. For instance, we reliably observe that institutional trust is in decline.

It is difficult to know how to feel about this decline in institutional trust though.1 Perhaps it represents an improvement in our epistemological hygiene. However, this interpretation seems foolishly optimistic. The prevalence of conspiracy thinking and other bonkers beliefs cuts sharply against this hope. Additionally, there is quite a bit of evidence to suggest that social trust is one of the bedrocks of economic growth. Even if we were somehow fostering a healthy public skepticism, does this come at the cost of scaling cooperation and improving our material circumstances? Bring on all the Noble Lies if so!

I cannot resolve this dilemma here. But the fact of this dilemma underscores the importance of the role of the public intellectual. These are figures of elite status with impressive educational or professional credentials who exit their domains of expertise and enter into public discourse. These figures must traverse disciplinary boundaries, evaluate the evidence behind high-impact findings or the quality of esoteric ideas and then synthesize these disparate components into a story that can be digested by the broad middle of a polity or at least some critical mass of educated people. Ideally, the stories promulgated by public intellectuals should have material or at least measurable benefits.

Unfortunately, our epoch is simultaneously a Golden Age and Dark Age for public intellectuals. There is perhaps no better time to try and make a living as one. The opportunities and platforms for building an audience that can be monetized abound. However, these same factors create incentives that ensure that many, if not all, public intellectuals will be corrupted by their own audience. It is also quite unclear if public intellectual discourse has been a net benefit or cost. Perhaps, this is why even our terms for public intellectuals have devolved: “influencer,” “talking head,” and “idea leader.”

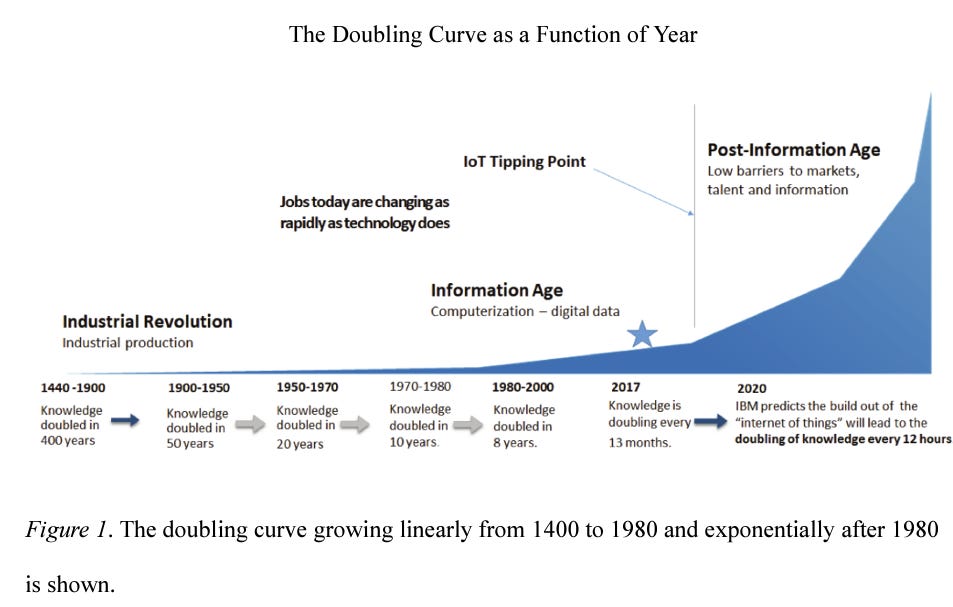

In many ways, all the issues above appear to be bound up with the information technology revolution of the 21st century. It is now a cliché to compare the invention of the internet to the invention of the printing press, especially when we include the chaos left in the wake of these inventions. Being cliché doesn’t make something untrue though. It is hard not to see the abundance of information and its exponential trajectory as both a blessing and curse, though I still lean toward the former view on balance. Nonetheless, it certainly raises the potential value of a figure that can analyze, synthesize, curate, and compress the information explosion.

One of the most prominent public intellectuals to attach himself to the challenges of the Information Age, is Yuval Noah Harari. His latest book, Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI is billed as a tour of information networks of the past and present. He is particularly interested in what we (humans broadly) should prioritize as our information networks increasingly become comprised of agents of silicon rather than of carbon. He is a soft-spoken cheerleader for progress, who also wants to emphasize shared human flourishing and to protect our status as the dominant intelligent agent of earth.

Before I present and examine some of the claims presented in Nexus (some of which I’ve previewed above), I want to examine the perception of Harari as a public intellectual. I think it helps illustrate the perils of the role. Harari himself is particularly anodyne and has largely removed himself from the platforms that are often to blame for the malign incentives that public intellectuals today face. In this way, his stripes are more of an old-fashioned type of figure. Nonetheless, he is still stuck in the same pit as the rest of them.

Harari, The Receptacle of Status Envy

My awareness of Harari began in 2017. This is when I got around to reading Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (2015) and started listening to the Sam Harris’ Making Sense Podcast.2 This preceded the predictable backlash to the book. It was in the year following its appearance on Barack Obama’s recommend book list too.3 Despite the obvious oversimplifications and the juvenile quality of some of the book’s provocations, I found Sapiens highly engaging as a read. It provided an awe-inspiring perspective on the deep human past, highlighting just how much of human diversity has been lost since the emergence of our species. Further, it properly highlighted many of the nearly magical innovations that propelled the success of our species, pointing out just how few of them were actually material inventions or due to material factors. In other words, the true power of humanity rested with its ability to coalesce around particular beliefs (intersubjective beliefs) and cooperate to achieve entirely imagined ends. To put it as simply as Harari did, Sapiens dominate because they create and believe in myths.

Harari’s follow-up books, Homo Deus (2017) and 21 Lessons for the 21st Century (2018), appeared with a rapidity that was obviously intended to capitalize on the blockbuster success of Sapiens. Subsequently, the quality of Harari’s writing declined some. Additionally, in an increasingly populist and nationalistic political moment, Harari’s political sensitivities were apparently piqued. Instead of expanding his praise of the power of myth, he increasingly began to warn of its dangers, working to deconstruct many modern mythologies while trying to express some sympathy for their origins or at least their originators.4 However, an eagerness to deliver political lessons usually begets annoyingly didactic prose. Plus, simplification about the complexities of science or even history are usually more acceptable to an educated readership than lectures about the politics of their particular place and time.5 Ultimately, this landed Harari in a pickle. The tastemakers, often of the poles of the Left or Right, put him in their crosshairs.

Among those on the mainstream academic Left, the complaints about Sapiens has earned him pejorative labels such as “guru” and “dangerous populist.” Among online conspiracy enthusiasts associated or identified with the Right and among online communists and socialists, his TedX or “Davos Man” aesthetics has earned him pejorative labels such as “neoliberal,” “globalist,” and “transhumanist.” Beyond the politically motivated attacks, I’m inclined to believe that Harari has mostly been a subject of criticism because of his wild success. His popularity has pricked the envy of other aspiring public intellectuals, especially because it likely seems there is nothing particularly original or insightful about his work.

I’m not particularly eager to target anyone, but I stumbled across an obvious case that I think is worth highlighting here. There is a British science communicator named Adam Rutherford who has authored a few nonfiction science books. Most of these books have doubled as political tracts that attack alleged modern iterations of eugenics or at least are concerned with debunking myths about racial hierarchy and/or innate differences between races.6 Interestingly, Rutherford seems particularly eager to denigrate Sapiens, posting in snide ways about it with some regularity. His specific objections to the arguments or claims in the book are never provided in detail though. He also has promoted a critique of the factual errors in Sapiens that appears to make worse factual errors.7 In fact, the errors the piece makes are in Rutherford’s supposed area of expertise, genetics!

Although some of the specific criticisms offered about Sapiens or Harari have merit to them, I think the intensity of much of the criticism is unwarranted.8 His work and ideas fall within what we usually find in popular nonfiction targeted at the median or broader segment of educated or intellectually curious individuals. We should perhaps ask if we should expect more from our public intellectuals and be more reticent to reward simple storytelling. This is likely an unreasonable ask though. There are more rigorous and sophisticated alternatives already available. There is also the primary research and scholarly publications themselves. Again, the very purpose of the public intellectual is to translate these more sophisticated sources into something acceptable for mass consumption. This is even valuable to highly educated experts in particular disciplines, who need accessible tours through related or distant disciplines. There are better and worse examples, but whining so vehemently about the particular success of one case reveals an off-putting level of envy. What does it actually achieve? Additionally, if there is indeed a fatal amount of substantive criticism that can be dealt a popular work, it will undoubtedly emerge and eventually a critical mass of intellectuals or the lay public will recognize this.9 A great deal more misleading or incorrect information will likely circulate on social media or in everyday conversation than within the pages of popular nonfiction works.

All’s Well that Gladwells

As should be evident already, I don’t want to come off as hyper-critical of Harari, but I also don’t want to let him escape criticism either. I’m certainly a partisan for raising the level of science communication and nonfiction writing, but I also understand that this will likely put-off many readers and limit the maximum impact of any given piece of writing. The reach of one’s work is a legitimate thing to care about. Popularity may seem like a superficial value, but in this case, writing that is read by no one doesn’t really exist. It is in the same category as ephemeral thoughts that never escape one’s lips, yet the cost of the creation of those words is so much higher. There is also the economics of it all. There is little incentive for major publishing houses to greenlight works without a prospective readership. Publishers already greenlight a lot of books that are guaranteed money losers. In some ways, we should expect popular nonfiction to hover around the quality it is now. In fact, it is perhaps better than should be expected based on the current set of incentives in publishing. Let’s accept that and offer feedback that can move it in a positive direction within these parameters.

And before I get to Harari’s book, I would like to give the pedantic criticism of Harari’s writing style its due. He does very much works within the Malcolm Gladwell paradigm of nonfiction writing, which privileges sensational and entertaining storytelling and exciting speculation over sober analysis and scholarly precision. There is effective and popular nonfiction that does less of this. Harari isn’t the biggest offender on this front though.10 But Harari is not going to provide all the evidence to support his claims in footnotes and references. He is liable to make some mistakes here and there. He isn’t going to go through all the twists and turns of the research record. He is going to rely on vignettes and metaphors to get his points across. In a lot of ways, this is smart writing. It will connect with more people. However, it will also ignore a great deal of complexity.

Alright, we’ve accepted the constraints on public intellectuals, let’s look at Harari’s latest, Nexus.

The Nexus of Carbon and Silicon

Harari’s latest book, Nexus, has many of the strengths of his monumental bestseller Sapiens as well as many of its weaknesses. In strengths, its scope is sweeping, the questions are existential, and the answers are satisfyingly simple. In weaknesses, its scope is sweeping, the questions are existential, and the answers are satisfyingly simple. Hopefully, my point is clear. We’ve been over this territory.

After finishing Nexus, I was particularly unsatisfied. It seems Harari is just playing the hits again, Lynyrd Skynyrd crooning “Free Bird” for the fifty bajillionth time. There are aspects of this that work though. Harari is once again eager to point out that fictional narratives hold modern societies together and keep social institutions functioning. This is a dorm-room tier epiphany, but it is also something that belongs in popular science writing. It is both obvious and profound that transmittable cultural packages are the special sauce of humanity. What’s really of interest here are the ingredients in the secret recipe. Sapiens does a reasonable job at tackling many of these, which is why I strongly recommend the work to any intellectually curious youngster. On the other hand, Nexus is significantly less interest in its subject, information networks, than Sapiens was in its subject.

The justification for Nexus is the impending transition between information networks comprised of humans (carbon) versus those comprised of machines (silicon). To heighten the impact of this question, Harari panders to some laughably midwit doomerism about the threats of artificial intelligence (AI) or algorithms in general. The entire discussion of the dangers here seems to miss that human decision-making falls prey to the same perils and that ultimately there are undesirable tradeoff that we can’t avoid. In fact, we hardly are shown what the possible upside is for putting silicon actors in our information networks or how we should understand value in a world that is increasingly digitized.

Harari begins the book by laying out two different theories of how information networks should function and implicitly argues for a middle position between the two. He contends that most of us have a reflexively "naïve" understanding of information. In other words, we often believe that the freer and more abundant information becomes, the closer to the truth and utopia we get. He contrasts this "naïve" understanding with a "populist" understanding of information (the proper label here should be "instrumentalist"). To a populist, information is a means to an end. Information is subservient to the agenda of power. Those in power must then control information and make their own realities. After contrasting these two very simple models of public epistemology, Harari sort of punts on formally defining what information actually is. He settles on the claim that information is anything that connects a network, which doesn’t seem like a proper definition at all. Then, he argues that the purpose of information networks is to discover truth and create order. These goals can often be in tension. After priming readers with this unsettling tradeoff, he jumps into the content of the book, which is divided into three parts.

In part one, Harari broadly covers the history of human information networks. This focuses on the two principle forces for building large-scale information networks: mythology and bureaucracy. The former inspires people to cooperate and build together, while the latter coordinates the formal maintenance of the network by setting its rules. Harari believes that both incur truth penalties for the sake of order (think of Plato's Noble Lie here) so it remains unclear to readers just how exactly truth is arrived at or how we know its there. To distract readers from this conundrum, Harari redirects us to the idea of "self-correcting mechanisms" built into information networks, which he raises with respect to how science has functioned historically. He argues these mechanisms are what keep information networks doing good things like effective and fair governance and so on.

In part two, Harari examines an emerging type of information networks - the inorganic network. This refers to information networks which are either not entirely comprised of human agents (e.g. the internet) and those that have no human agents at all. Harari proceeds to over-embellish a number of things about AI in order to do some fearmongering. There is also a lot of the usual whining about the problems with the architecture and incentives of social media and our modern business models in technology. I’m generally not jazzed by these complaints because it is unclear what the alternative is supposed to be. Additionally, it is clear that this somewhat underhanded business model allows for a lot of value creation an low cost. There is perhaps some failure of imagination and cooperation concerning the monetization of personal data. There have certainly been attempts by governments and corporations to intercede on this, but these attempts appear abortive. I think it would have behooved Harari to examine this question more closely.

In the final section, Harari explores different strategies that humans could use to manage inorganic networks. This is mostly just a soft polemic about how humans needs to rise up to control technology to reach the ends we want to. I agree with the message that technology should serve our ends, but I also am not particularly convinced that AI is going to subvert our aims or be the source of any more chaos than we already face for very human reasons. The big issue the anodyne idea that technology should serve humans is that different humans want different things and often a few motivated actors will ultimately decide how a technology is developed and implemented, and this will likely have important effects on all of us. Harari explores this on the level of centralized governments, using surveillance to control its polity, but he fails to imagine the ways in which private interests may conflict with each other within emerging information networks. Personally, I think there is some upside to these conflicts too and that if we work to squash all the motivated individuals or small groups this may come a greater long-term cost.

Despite my critiques, I think Nexus is another generally edifying book from Harari for general readers, especially those new to these ideas. There is a lot of interesting history, especially in the first part of the book. Harari appears to have a habit of front-loading his books. Harari remains an effective storyteller and an important public intellectual in our time. However, he does offer little to those who are already versed in the topics he writes about except the odd vignettes drawn from his own domain expertise, medieval and military history. It is also easy to digest the thesis of his book by reading a summary like mine or listening to an interview of him on any podcast out there. I encourage readers to engage with his ideas in good faith and also seek alternative perspectives on emerging technology.

Conclusions

Big ideas are exciting and our future is bound to be interesting. It is worth thinking about these things in the here and now. We should try to incentivize our public intellectuals to be both as rigorous and as creative as possible, while still allowing them to serve the function they’re meant to serve (i.e. they’re not meant to be domain experts and deliver perfectly calibrated insights from one discipline). We should also be understanding of the current incentives in place and that they are not optimized at the moment. Those who attack currently popular public intellectuals are generally contributing to the same system of malign incentives or merely seeking to ascend in the status game themselves. Obviously, I think this is counter-productive. Valuable criticism is worthwhile but should be offered in the mode that we hope our current set of public intellectuals to emulate. Members of the audience should also be more willing to reward rigor, sophistication, and nuance than they are today. Hopefully, we navigate the disruption of the Information Age with more wisdom than prior information revolutions.

If you enjoyed my thoughts on Nexus, check out my mini-review of Sapiens on Substack Notes:

My comments on a related piece on public intellectuals on Substack Notes:

My personal inclination is that it is a bad thing. I don’t think it is a crisis, but I think it is already levying penalties on some of our social institutions.

Sam Harris is another public intellectual whose project is quite similar to that of Harari’s. They both almost militantly secular left-liberals committed to a humanistic and progressive vision for our present and future. This often is accompanied by advocacy for practices like meditation or mindfulness, which look like secular substitutes for religious rituals.

This zenith of acceptable liberal reading.

This isn’t to say that Sapiens didn’t contain a lot of the usual caveat and warning about myths gone awry.

The latter is sure to trigger a lot more self-consciousness about Gell-Mann Amnesia.

This isn’t a particularly new bit for left-of-center public intellectuals in science communication. The sociobiology wars stretch back to the 70s, and Franz Boas was obviously working to move anthropology dramatically leftward as a discipline well before this.

For those interested in the errors I’m referring to in the Current Affairs piece: The piece implicitly references genetics research on polymorphisms and the MAOA locus. These findings were likely false positives from what’s known as the “candidate gene study era” of genetics research. During this time, there were a lot of false positive findings because geneticists hadn’t yet learned that very large sample sizes were needed to study the effect of common genetic changes on complex traits. The other genetics-related error this piece makes is endorsing the transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (TGEI) hypothesis. This is a popular resurrection of Lamarckian inheritance that has little to no direct or mechanistic empirical evidence. For more on the issues with claims about TGEI I recommend reading Kevin Mitchell’s blog on the subject or this review piece.

This is common to see with many of our other popular public intellectuals, including Steven Pinker, Jared Diamond, Sam Harris, Jon Haidt, Francis Fukuyama, etc. They’re typically taking one big idea (That One Thing That Explains Everything - TOTTEE) and using it to illuminate or explain many salient phenomena. These are simplified stories that by their nature will get some part of the story wrong and thus are vulnerable to attack. Those most interested in attacking these ideas are the public intellectual aspirants who would like the same level of clout as these figures. I think the existence of these types of works are on net positive because they drive interest in intellectual subjects and the criticism that usually nip at the heels of the work round out the conversation. If there is fatal criticism, this usually supplants the work itself. A good example of this is Noam Chomsky’s review of B.F. Skinner’s book Verbal Behavior.

This is perhaps a naïve belief, but I feel like I’ve seen this in action before.

For instance, I think the author behind the eponym is worse on this front than Harari

Just like you I also read Sapiens after the hype-wave but before the backlash and got really frustrated with the intellectual hipsterism of all the people pretending to be so far above it. I think you hit the nail on the head here. "Dorm-room tier epiphanies" aren't a bad thing, and broad appeal public intellectuals are important. Sometimes I worry that the primacy of sneering, dunking, and debunking on social media is a way more destructive information environment than the idealistic TED-talks I grew up on. Like you get the impression that everything is bullshit all the time, except hopelessly niche books that you'd never find the energy to read (and if you did you'd lack the prior knowledge needed to understand it). I wouldn't be surprised if that atmosphere would make some people retreat from intellectual curiosity completely.

Makes me want to read some Harari!