Discover more from Holodoxa

The Evolution of Fatherhood

In her new book, Sarah Hrdy's explores the natural history of paternal care, describing the underlying behavioral endocrinology and speculating on its evolutionary origins.

Man is the rival of other men; he delights in competition, and this leads to ambition which passes too easily into selfishness. These latter qualities seem to be his natural and unfortunate birthright.

-Charles Darwin, 1871

My unexpected finding is that inside every man there lurk ancient caretaking tendencies that render a man every bit as protective and nurturing as the most committed mother.

-Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, Father Time (2024)

As the epigraphs from Darwin and Hrdy above suggest, the evolutionary sciences were birthed with a traditional understanding of sexual difference in parental proclivities and abilities. This harks all the way back to observations made by Darwin. He and many scholars in his lineage have recognized that each sex is induced to sail along different currents in the mating seas. Males must find the biggest wave and surf to its crest to garner attention from desirable females. Females must choose the male most likely to be able to provision and protect her for the long, perilous sojourn through pregnancy and motherhood. The different interests of the sexes is inevitably a source of tension, especially when environments become harsh, the ratio of males-to-females become imbalanced, and the young remain resource intensive. Many in the behavioral and evolutionary sciences believe that extended commitment - whether resources or care - from fathers in exchange for certainty of paternity (now today’s marriage and the nuclear family in other words) was a grand compromise in the battle of the sexes in hominids. This compromise has sustained and perhaps propelled the human species. Yet, many still debate how innate versus learned monogamy plus shared parenting is in primates and to what extent it is a product of or a counterweight to male-male coalitions and their subsequent dominance over material resources (i.e. patriarchy).

Often built into beliefs about evolved sexual difference is the assumption that the monogamy compromise is a bit unnatural or at least unstable. The male of the species must in his heart of hearts rebel against sexual monotony and the bonds of domesticity, yearning to exert dominance and spread his seed, while the female of the species in her heart of hearts must agonize about whether her mate choice was optimal, eagerly awaiting an opportunity to upgrade. Typically left out of discussions about sexual difference is whether males may possess a nurturing instinct for themselves. And if they do, how exactly is it activated? Because it certainly doesn’t appear to be the default setting at least in much of our ancestral and present environments.

The eminent sociobiologist Sarah Hrdy thinks it is time to reconsider our evolutionary narratives about the care instincts and nurturing capacity of males. The prospect Hrdy raises is quite a revision to the received understanding of human nature, especially given the mountains of empirical reports, chronicling the status-seeking, violent (often infanticidal), and selfish behavior of primate males. In fact, Hrdy has assembled many of these chronicles herself.1 To defend this revision to human nature, Hrdy has authored a new book, Father Time: A Natural History of Men and Babies.2

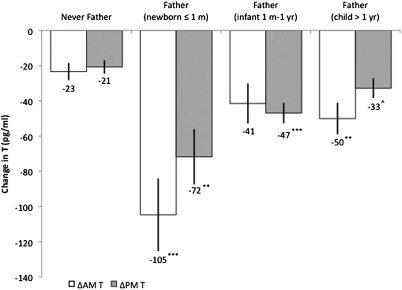

Inspired by witnessing the dedicated care provided by the fathers of her grandchildren3, Hrdy dove headlong into the emerging research on paternal care on a “quest to learn when and how nurturing emotions arose in males and to identify what it takes for them to be expressed.” Hrdy’s quest takes her through millions of years of evolution and a survey of paternal care across many species. At her destination, she believes she’s found an ancient caretaking tendency located in every man that simply awaits activation by particular triggers. Hrdy believes the most important of these triggers is proximity to babies4, which drives an endocrinological response that is similar yet distinct from that of mothers. This paternal endocrinology includes a drop in testosterone and cortisol with concomitant spikes of oxytocin and prolactin.5

Interestingly, Hrdy is fairly adamant that modern paternal care cannot only be a change forced upon fathers by cultural, technological, and economic changes. Many factors external to biology are important in shaping the expression of paternal care, but she is adamant that it has a biological substrate. This compels her to review many different lines of evidence beyond just human endocrinology. She turns to her wealth of knowledge in anthropology and primatology.

The Deadbeat Dads of the Animal Kingdom

Given a quick glance at the behavior of great apes, the prospects for generous fatherhood in humans looks pretty grim. Infant care by males is nonexistent in our closest evolutionary relations, including chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and even bonobos.6 A broader look at the class of Mammalia provides little reassurance about a possible deep paternal instinct either. At most 5% of the world’s 5,400 mammalian species have any direct male care of babies.7 From this vantage point, it seems extremely remarkable that dads are invested as they are in care. Given the above, it’d seem wise to bet evolution has carried forward more paternal aloofness than paternal care in humans.8 Hrdy, however, is less discouraged by this record, reaching even deeper into the evolutionary past for examples of paternal investment.

There are of course some striking cases of paternal care in the kingdom of Animalia. Hrdy records many of these in her book. The most famous example is perhaps male seahorses who incubate developing embryos in their tail pouch. There are other instances, especially in fish and amphibians, that range across different classes and orders even up through primates. Species survival appears to have periodically required that males do more than compete for mates but also sacrifice for their young. It seems that harsh environments have been especially instrumental in these cases. Hrdy sees these examples as confirmatory in terms of a deep biological predicate for fatherhood.

In a somewhat concerning portion of the book, Hrdy presents what she sees as the most convincing evidence of evolved paternal care by citing live brain imaging (fMRI) studies of parents with infants. When this research has compared new mothers and fathers, the general finding has been that mothers’ brains show activation in primordial regions while fathers show activation in higher-level regions. This conclusion suggests a more innate maternal response and a more compensatory paternal one. The issues for the investigators is they were concerned if the observed paternal response was just a function of fathers being secondary rather than primary caregivers. Subsequently, a design comparing gay adoptive fathers to biological fathers and mothers was conducted. This study and other related research found that the areas of the brain activated in gay fathers is roughly the same as in biological mothers.9

There are a number of reasons to be a bit dubious about these findings though. First, there are some fundamental limitations with fMRI as a tool that tend to lead investigators to overinterpret results conveniently.10 Second, the study of interest is reliant on small sample sizes. Third, the study design can’t actually confidently draw the conclusions it does. There are alternative explanations that may account for the observations, such as ascertainment bias or confounders. It doesn’t mean that the data themselves should be dismissed wholesale, but they should play a smaller role in Hrdy’s argument. Some of the motivation here seems to be a desire to argue that men can be just as attentive and caring as mothers. This isn’t the best data to support such claims.11

Although the picture of fatherhood in the animal kingdom is a bit bleak, it is abundantly true that fathers today are sometimes heavily invested in the care of infants and children. In WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) societies, fathers are often involved in ways rivaling mothers. And across human societies, there is frequently some sort of provisioning or indirect support provided by a father to his children. Hrdy points out this occurs in more ancestral niches as well. She highlights Barry Hewlett’s findings on paternal investment in the Aka, a group of Central African foragers. Aka men spend 50% of a day within arms reach of infants and interact with them fondly ~10% of that time. They also hold young infants (1-4 months of age) for almost a quarter of that time.12

For Hrdy, the combined data from the evolutionary record, behavioral endocrinology, and brain imaging suggest the paternal care so abundant in humans must be part of our evolved biology. In technical terms. “an evolutionary ancient alloparenting substrate” must be shared by all humans. It is simply a question of activating it. Although this claim seems self-evident to me, it does compel an explanation. Hrdy doesn’t disappoint, though her explanation zaggs a bit from the traditional evolutionary explanation of fatherhood.

The Biological Origins of Fatherhood: Sexual and Social Selection

It can be tempting for social scientists to assume that what is happening is entirely due to culture. After all, in the life of every individual, historical, ecological, economic, and social forces construct the contexts in which they interact with others. Yet what individuals do also has physiological precursors and consequences.

~Sarah Hrdy p.85

There is a bit of a false conceit to Hrdy’s book. She feigns quite a bit of ignorance about a subject connected to ideas she’s studied for the entirety of her illustrious career.13 She introduces the book’s central question, the evolutionary origins of human paternal care, as if the question has been ignored and left largely unanswered. In some ways, the setup can be rationalized, but the reader will be in for a jarring surprise when Hrdy switches tact. She goes from trying to solely account for the evolution of paternal care as a neglected yet important anthropological question to trying to wrestle with the existing model(s) offered by her field. What is sociobiology’s evolutionary model of fatherhood? Well, it is largely an extension of the aforementioned dynamics of sexual selection.

As noted above, the males of our nearest extant ape relatives are almost entirely removed from care of the young. This is thus reasonably assumed to be a behavioral feature shared by our most recent common ancestor circa 7 million years ago (mya). It is also not particularly hard to find evidence that human males can be quite aloof or negligent as dads even today.14 Nonetheless, there is still a plausible evolutionary story for how human males at least became more involved as dads. The archaeological record suggests that this began to change during the early Pleistocene (2.6 mya - 12 kya) as hominins began to consume meat. The presence of meat in the diet obviously implicates the development of hunting and with it eventually techno-complexes around butchery, preservation, and cooking. These developments would change a lot about the dynamics between men and women, linking their daily lives closer together. The relationship between resourcefulness and status in males would become clearer to the chooser of mates, females. Female hominins could then choose a particular male as a provider and provide him guarantees of paternity by granting only him sexual access. Over time, the “food in exchange for paternity” trade would increase reproductive success by eliciting men relatively more in the care of the young. More intense sexual selection and more nutritious calories are thus enlisted as explanations for both paternal investment and rapid gains in brain volume and intelligence in humans.

Hrdy is not satisfied by the invocation of sexual selection alone as the origin of paternal care. She argues that the available estimates of the caloric needs of children (13 million calories prior to independence) and the sourcing of calories (perhaps a majority from predominantly female foraging) during this evolutionarily sensitive time in the history of fatherhood make the hunting based model untenable. In other words, it isn’t plausible to believe that hunting alone could have sourced enough calories to sustain “the sexual contract.” Hrdy instead favors the idea that the harsh environmental conditions and increased needs of offspring (along with changes like concealed ovulation and shorter inter-birth intervals) during the Pleistocene put “social” selection pressure on males to find other ways to be supportive of females, which would include paternal care. There was increasing interdependence between the sexes. To support this claim, she cites ethnographic evidence derived from extant hunter-gatherer groups in today’s East African, such as the Ju/’hoansi. The argument also fits nicely with the paternal care example in the animal kingdom, such as the prairie voles and Marmosets, where environmental pressures or increased offspring demand enlisted paternal care.

Interestingly, Hrdy takes her argument a bit further beyond her critique of sexual selection narratives about fatherhood. She argues that the social selection pressures that increase male and female interdependence also changed the developmental context of youngsters. This may have created selection pressures that favored more sympathetic and charismatic young. This selection for “other-regarding” behaviors may have been pivotal in brain evolution, creating the selection gradient necessary to reach the intelligent abilities of modern humans.

Hrdy’s explanation is an interesting critique of the narratives of sexual selection. However, I do fear it is also a bit thinly evidenced. In the traditional narrative or Hrdy’s narrative, we have little evidence for any selection for paternal care or anything particularly distinct about paternal care in terms of its biological substrate. I think Hrdy aptly demonstrates how the latent care capacity in male hominins could have been activated and then likely instantiated in durable folkways, but not that it has been shaped by evolution much. This story would be very much one of gene-culture co-evolution rather than evolution alone. In some ways, this is still her claim, but I think noting this different framing is important.

The Longhouse Awakens Paternal Instinct

In online right-wing discourse, “The Longhouse” is a shorthand way to refer to a social regime in which a certain type of female value set has come to dominate social institutions.15 This metonym harkens back to the design of living quarter of certain native American tribes and is a reference to how that space empowered female gossip as a mechanism of social control. As can be surmised, use of the term is often derogatory or at least tinged with ironic disdain. In light of Hrdy’s book, it is interesting that this term has found such purchase among those on the online right. If we’re to take Hrdy’s thesis about paternal care as accurate, then it is indeed social technologies like The Longhouse that activate paternal care. It is possible that the alternative to “the soft authoritarianism of the Longhouse's weepy moralism” is vicious status competition between men, the kind that results in rampant destruction.

This is not a particularly flattering view of men. It also still casts women in a sacrificial social role, one in which even advances in reproductive technology would not be freeing. Although not explicitly stated, Hrdy ostensibly believes that social technologies are required to muted man’s violent and selfish tendencies by activating his latent care instinct. The pioneers and sustainers of these social technologies are women even when care in men can be readily activated. Hrdy does gesture to modern social and technological developments as salutary on the care activation front. I too think there have been a lot of salutary development over both the long-run and short-run of history for human cooperation, but I’m not sure how much these development can guarantee male independence with women and proximity to infants. There are some changes on the horizon to suggest young men and women are increasingly estranged from each other and total fertility has been in steady decline across almost all wealthy nations.

My Paternal Ramblings

As a father, Hrdy’s claims about the physiological and behavioral changes wrought by proximity to and care of babies largely resonate with me. Fatherhood has transformed me. However, I’ve experienced fatherhood as motivating in both caring and competitive dimensions of my personality. I’ve also experienced it as an intentional, rational commitment. While I feel quite a bit more than the “quantum of tenderness” that Mother Nature (Hrdy’s metaphor for evolution) has allotted my sex, I’m not sure how different my behavior would be without this natural response. As in, I envisioned doing and planned to do the things I now do as a father. Did I actually need the physiological transformations of close contact with my children to care for them in the way I do today? I think I can confidently answer, “No!” But perhaps, I think I know myself better than I actually do.

I guess what I’m saying is that even after reading Father Time I still wonder how much the latent biological substrate matters to the behavior of fathers. Although Hrdy agrees that cultural and technological change have mattered a lot as well, it is unclear whether any of it is actually necessary to produce fathers. Despite all our knowledge of human nature, it is unclear just how naturally brutish man is, how much this has change over our history (plenty to suggest we’re less violent than our ancestors but it’s debated), and how much the male proclivity for violence varies over the population. It seems like there could have been and still be a lot of things that domesticate and/or pacify men so that we act less troglodytian. I think Hrdy’s narrative has unfortunately largely overlooked these considerations. Additionally, I’m not entirely convinced the latent substrate is a greater and more consistent inducement that paternal certainty (i.e. the forces of kin selection). Hrdy’s narrative downplays just how important relatedness is both for predicting individual behavior but also for understanding the social dynamics of a group.

Although I have my share of critiques of Hrdy’s theory of paternal care, I thoroughly enjoyed Father Time. It was an edifying tour of the evolution and biology of fatherhood. This is a distinct perspective on the long history of an increasingly salient social role in today’s world.

Hrdy’s graduate thesis concerned infanticide in Langurs, arboreal old world monkeys. This work was eventually published as a book, The Langurs of Abu: Female and Male Strategies of Reproduction.

Published by Princeton University Press in May 14, 2024

Hrdy’s book is filled with personal anecdotes about the paternal care provided by her son-in-law as well as her own son Niko.

According to Hrdy’s read of the anthropological literature, the two main factors that shaped increasing paternal investment over the Pleistocene were family structure and subsistence modes.

The response she describes in an anecdote in which she tests herself and her husband before and after they care for their grandchildren shows the paternal response has a bit of a delay to it but eventually is quite similar to the female endocrinological response.

Hrdy’s claim.

Hrdy borrow the high end of an estimate from Rogers and Bales (2019) which was based on survey of 2545 species by Lukas and Clutton-Brock (2013).

Hrdy does address herself to paternal aloofness in humans in the book, but it isn’t examined too closely.

This is not strictly true in my read of the Feldman data. The gay fathers still have STS activation like straight fathers.

Additionally, I think any reasonable look at the data would suggest that men are not as apt at care as women despite clearly have a capacity for it.

This finding is highlighted because it is a remarkable outlier rather than what is normally observed in H-G groups.

This is before we mention that Father Time itself is a result of a ten-year long project.

In America, for instance, the rate of births to single mothers hovers around 40%. Although many of these fathers still support their children in some way, it is estimated that around one-third of nonresident fathers do not provide any support to their actual biological children.

In more common parlance, “women’s tears” is more often invoked to refer to similar phenomena. This usage, though still popular in online right-wing discourse, is hardly confined to it. In fact, racialized version of the term are frequently invoked by anti-racist activists.

Subscribe to Holodoxa

A study of the total human condition. I examine ideas from science, literature, technology, politics, and more. Most posts will consist of book reviews or short essays.

> Despite all our knowledge of human nature, it is unclear just how naturally brutish man is, how much this has change over our history (plenty to suggest we’re less violent than our ancestors but it’s debated)

I thought we actually have decent grounding here.

For hunter gatherer males before agriculture, the rate is something like 30-50% chance of violent death in their lifetime. If you put it in terms of violent deaths per 100k, they're averaging about 1030. Some of the most warlike HG tribes we've seen historically top at 1500.

> and how much the male proclivity for violence varies over the population.

For more recent non-state hunter gatherers 1800 - today they've come down to ~520.

Here's a table I made showing rates for one of my own substack posts:

https://imgur.com/a/J1bcPPG

And of course for modern states like Europe and the US, if you include homicides we're at rates between 0.2 (Japan), ~1 (most of Europe), and ~7 (USA) today.

This overall narrative arc of progressively reducing violence is basically the narrative in Stephen Pinkers Better Angels of our Nature.

> It seems like there could have been and still be a lot of things that domesticate and/or pacify men so that we act less troglodytian.

Yes, have you read Richard Wrangham's *The Goodness Paradox?* It's about our self-domestication as a species. Amazingly readable and accessible book, like most of his books. I think a combination of this and Geoffrey Miller's *The Mating Mind* covers the forces making us less troglodytian. Broadly, it's sexual selection for hundreds of thousands of years, then the Tyranny of the Cousins for a few hundred thousand.

This is directly contrasted with our confreres the Neanderthals, and our likely-ancestors H Heidelbergensis, who were not domesticated and so had massively higher testosterone, and likely much higher reactive aggression. This led to them having much lower group sizes, and our self domestication was like a super weapon that led to us wiping them (and every other) hominin species out in our last out-migration from Africa after the Cognitive Revolution 50kya.

I wrote about this in a different substack post, but don't want to seem like I'm spamming your comment section, so won't leave a link to any of them unless asked.

In terms of Neanderthal violent death rates per 100k, it's difficult to estimate, but if you count hunting accidents, it would be significantly higher than ours - they were more or less obligate carnivores, the majority of their diet was meat according to dentin studies, and so they had to hunt for food much more often than H Sap did, and their life expectancy was quite a bit shorter than H Sap hunter gatherer life expectancies. Contemporary HG's like the Hadza live to their mid 70's, and adult Neanderthals lived to their early 40's or so on average (so that's not the typical "medieval people only lived to 40" misunderstanding driven by high infant mortality), and the majority of skeletal remains found have signs of injury or violent death.

Thanks, interesting take on Father Time. I've just started reading Father Time when I came across your post. I've read several books of Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, she's a great scholar and an inspiring writer. Sarah Blaffer Hrdy: “Human males may nurture their young a little, a lot, or not at all” (Mothers and Others, 2009: 162). I am very curious how her journey got Hrdy from this universal truth to this point that you mention: "My unexpected finding is that inside every man there lurk ancient caretaking tendencies that render a man every bit as protective and nurturing as the most committed mother. After all: “Of all the casts of characters in this melodrama the role of the father is the most subject to creative script variation” - David Lancy (The Anthropology of Childhood - Cherubs, Chattel, Changelings, 2022: 131).