Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1

A quick primer

This article is part of a series on hereditary cancer syndromes and cancer genetics called Cancer Genomes. If new to the series, please go to my post “Introducing Cancer Genomes” for an explainer.

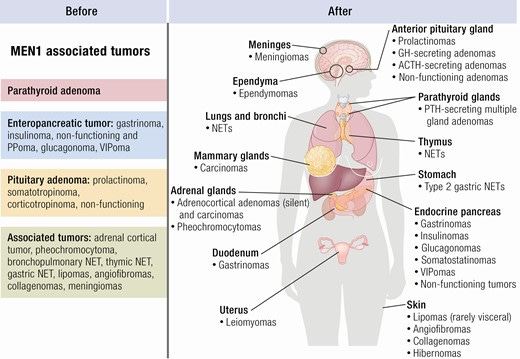

The cancer syndrome multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 emerged as the resolution to a clinical standoff. In 1954, the physician Paul Wermer reported a endocrine adenomatosis that showed a genetic pattern, giving his name to the syndrome. This was promptly followed by a report from doctors Robert Zollinger and Edwin Ellison of a case of intractable peptic ulcer with pancreatic islet adenoma. They also named their syndrome eponymously, “Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.” A little more than a decade later, it was recognized that these cases of multiple endocrine adenomatosis affecting the GI glands were one and the same. Thusly, the consensus designation became Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (MEN1). It was also around this time that scientists began to speculate that a single genetic lesion was the perpetrator and that the pattern of disease followed along with what’s expected under the two-hit model of tumorigenesis. However, the specific and full genetic etiology eluded scientists until the 1990s.

MEN1 is a rare autosomal dominant disorder caused by germline mutations in the tumor suppressor gene MEN1. Unfortunately, naming the gene the same abbreviation for the disease can create some confusion. So when I write “MEN1” I am taking about the cancer syndrome. When I write “MEN1” I am writing about the tumor suppressor gene that encodes a 610 amino acid protein called menin. Menin functions as a scaffold protein that facilitates the interaction of many different proteins participating in a wide range of cell biology, including gene expression and signal transduction.

Genetic Discovery of MEN1

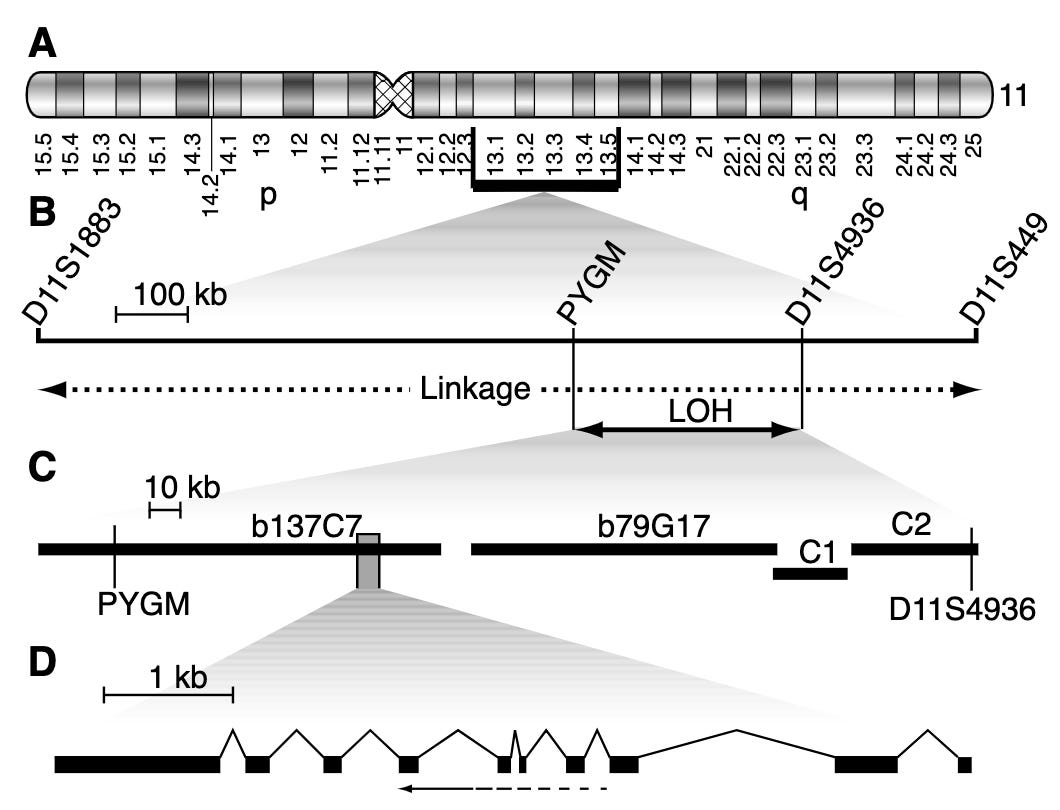

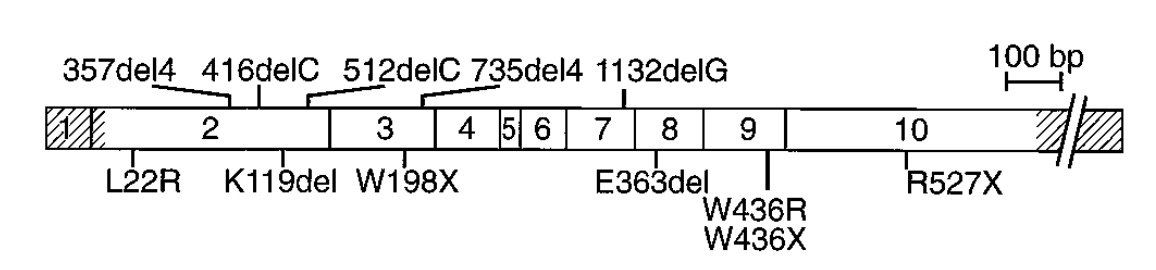

Several linkage studies spanning several MEN1 families identified a region of the long arm of chromosome 11 (11q13) as linked with the disease. However, it took quite a bit of additional study to narrow the linkage window and pinpoint MEN1 as the culprit gene. A number of erroneous candidates were considered. Finally, several studies in 1997 demonstrated that MEN1 was the definitive candidate. Chandrasekharappa and colleagues showed 14 probands from 15 affected families carried one of 12 different mutations in MEN1. Lemmens and colleagues confirmed this observation showing something similar in nine of 10 unrelated MEN1 families. This work was further replicated by Agarwal and colleagues who identified 40 different mutations in MEN1 in 34 unrelated affected families and 8 sporadic cases.1 Mutation in MEN1 was definitively behind MEN1 cases.

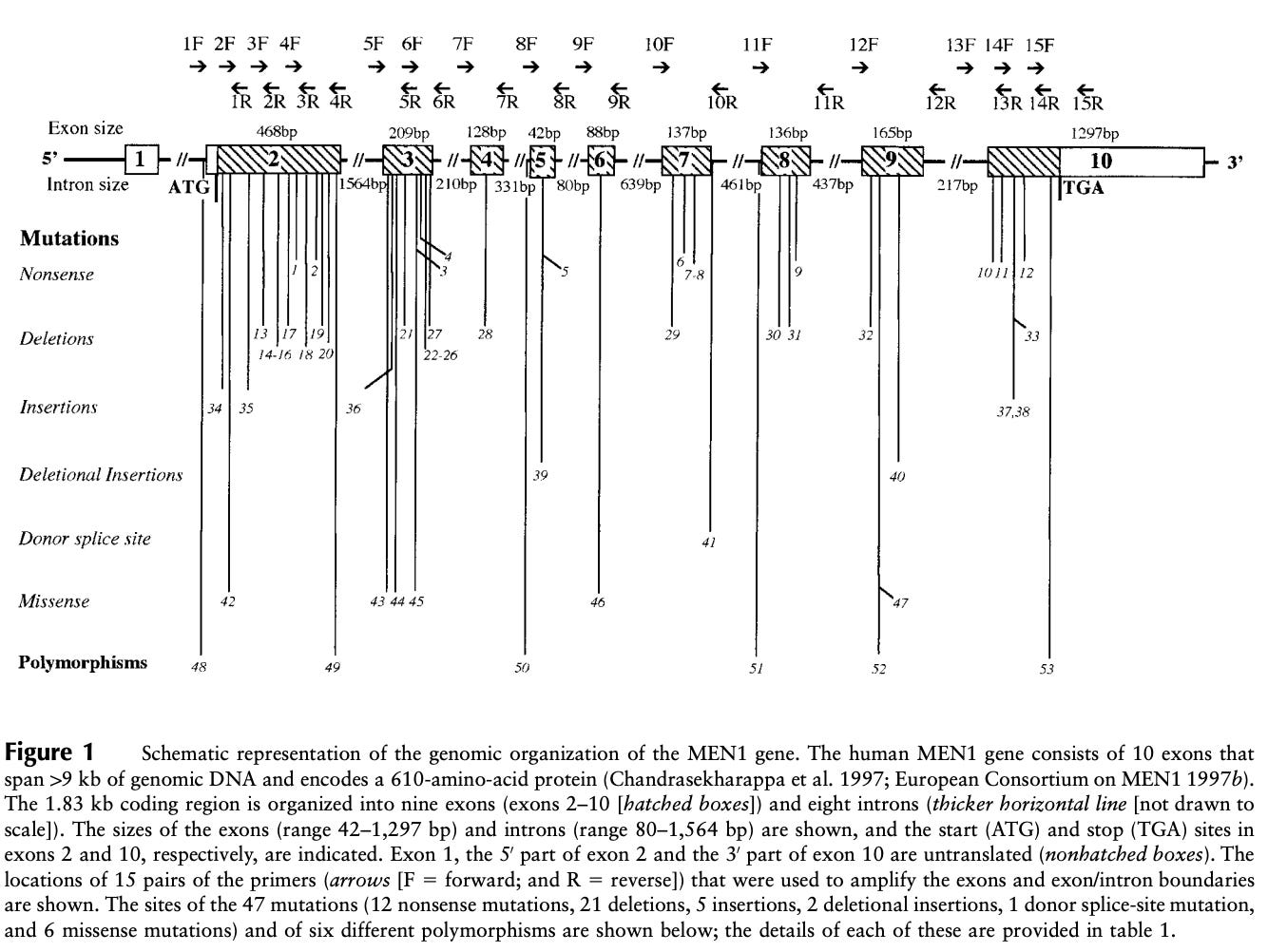

In 1998, a small survey of variation across the 2,790 base-pairs and splice junctions of MEN1 was conducted across 63 affected MEN1 families. The study identified 47 mutations distributed across the gene body. Five of these were de novo mutations, and four hotspot regions contained more than a quarter of all mutations. The survey also assessed the age-related penetrance of MEN1, which essentially reaches 100% by age 40. This means that by age 40 a carrier of a MEN1 mutation will shows some signs of endocrine neoplasia.

The genetic discovery of MEN1 was critical for MEN1 patients. A genetic diagnosis enables precision medicine strategies. In other words, physicians caring for MEN1 patients have distinct management approaches for patients that carry a mutation versus those that do not.2 However, in practices 90% of patients that receive a MEN1 diagnosis also carry a MEN1 mutation - an almost perfect genotype-disease match especially given the high penetrance.3 Unfortunately, there can still be quite a bit of variation in how the disease presents even within families, and this is poorly understood. Subsequently, an arduous screening and treatment regime must be applied to all carriers as this is expected to significantly improve survival outcomes. Substantially more aggressive clinical strategies are warranted for MEN1 mutation carriers because those negative for MEN1 mutation have delayed disease penetrance (~13 years later), less severe presentations, and better survival (87 vs 72 years-of-age). MEN1 cases without MEN1 mutation may carry mutations in other genes like CDKN1A, CDKN1B, CDKN2B, CDKN2C, CDC73, CASR, RET, and AIP.

Therapeutic Options in MEN1

The multifocality and metastatic potential of tumors in MEN1 often preclude surgical intervention or limit its utility. This and the possibility of delaying surgery or proactively controlling disease highlights the importance of drug treatments in MEN1. Unfortunately, there have been few clinical trials to rigorously study the efficacy of the use of drugs in MEN1. Subsequently, physicians are left to extrapolate from the lessons learned in the treatment of sporadic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). Treatment option for MEN1 can be divided into targeted therapies and chemotherapies.

Targeted therapy

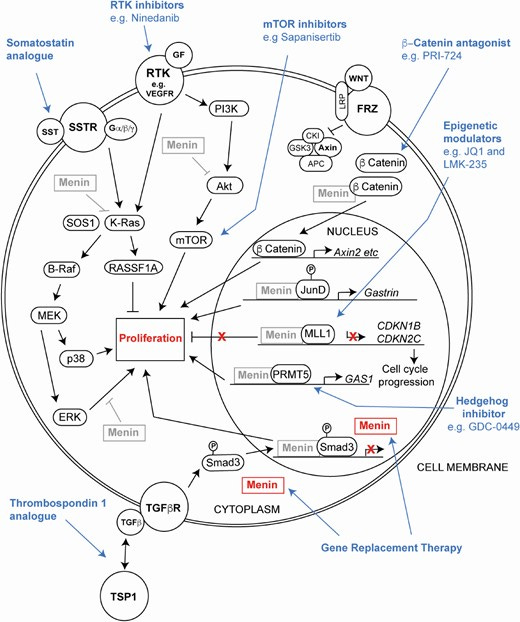

Targeted therapy definitionally hits a specific tumor-associated target. Pharmacological targets often include receptors or important effectors of a signaling transduction cascade. For NETs, this includes the somatostatin receptor (SSTR), mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), and various receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) especially vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) and platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs).

SSTRs can be targeted with somatostatin analogues (SSAs) like octreotide, lanreotide, and pasireotide. These are typically the first line therapy and are effective at reducing tumor burden and restraining the hypersecretory activity of the NETs. Some clinical study of SSAs has occurred in MEN1 patients and has consistently shown benefit. An additional advantage of SSAs is that they can be linked to radionuclides to deliver radiation in a targeted fashion.

Inhibitors of mTOR like everolimus are also options for advanced NETs. Everolimus has been shown to more than double the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with metastatic NETs of the lung and pancreas. Further study of mTOR inhibitors is needed to understand if they can be used in earlier treatment lines for NET patients or maybe even prophylactically in MEN1 patients.

Because NETs tend to be highly vascularized, they are theoretically vulnerable to RTK inhibitors that damp down the signaling responsible for growing blood vessels. Two traditional tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for NETs are sunitinib and pazopanib. Both have been shown to improve PFS in pancreatic NETs. However, little is known about whether these TKIs offer any benefits to MEN1 patients. There is likely quite a bit of room to improve upon TKI options and combination thereof for MEN1. The challenge is developing clinical trial designs that produce actionable insights as there is such a small study population.4

Some MEN1 patients with parathyroid tumors where surgery has failed or is contradicated may be treated with a drug class called CaSR agonists. CaSR agonists like cinacalcet may improve hypercalcemia and primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT).

Chemotherapy

Almost every class of chemotherapy has been used in the treatment of NETs: alkylating agents, antimicrotubule agents, topoisomerase inhibitors, and antimetabolites. However, chemotherapy tends to be reserved for patients with metastases, high tumor burden, or high proliferation indices. The benefits of chemotherapy for MEN1 patients remains unclear.

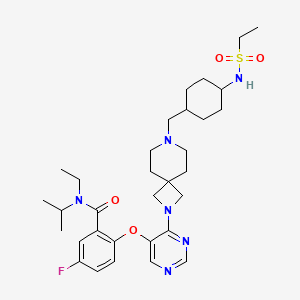

Recently, there has been a significant increase in our understanding of menin function in a cancer context thanks to study of MEN1 tumor models. This has helped contribute to a proliferation of novel, investigational therapeutic options: gene replacement therapies, epigenetic targeting therapies, Wnt pathway inhibitors, and novel small molecule inhibitors. In fact, there is a drug that is approaching market approval that targets menin, revumenib. However, this drug is unlikely to be useful in the treatment of MEN1 patients as it is being explored in relapsed or refractory acute leukemias that are driven by KMT2A fusions. Surprisingly, menin is functioning more as an oncogene than a tumor suppressor in this context. It interacts with the over activated KMT2A (also known as MLL) to drive expression of genes that help the leukemic cells survive and proliferate. Nonetheless, clinical evidence that menin can be therapeutically targeted should inspire hope and activity in scientists looking to develop options for MEN1 patients. Based on the already ongoing activity, this appears to be the case.

MEN1 vs MEN2

In contrast to Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2 (MEN2), which was a recent entry in the Cancer Genomes series, MEN1 cases present more diversely. It isn’t well described, but this may even be true within families. There has been reports of identical MEN1 twins with quite different disease manifestations.5 Beyond simply being intriguing, this suggests somatic evolution within MEN1 individuals is critical to disease presentation. Additionally, there are not distinct facial features associated with MEN1 nor are there quite characteristic tumor types (e.g. medullary thyroid cancer). Additionally, the genetic lesions driving MEN2 activate an oncogene RET, while the genetic lesions driving MEN1 deactivate a non-traditional tumor suppressor gene MEN1. Together MEN1 and RET explain most familial and sporadic cases of multiple endocrine neoplasia yet it remains unknown why these two broadly expressed genes quite specifically influence proliferation of neuroendocrine tissue. Despite our strong understanding of the genetic etiology of MEN-related disease, future research should explore the hazy unknown between the inherited lesion and clinical presentation. Such research helps realize the full power of genetic knowledge.

The unaffected families included in these studies are thought to have a separate clinical syndrome with a different genetic etiology. Some form of familial hyperparathyroidism.

As with many cancer syndromes, there is some discrepancy between a clinical diagnosis and a genetic one. In this case, 2 or more MEN1-associated tumors yields a sporadic MEN1 clinical diagnosis. For patients with a family history (first degree relative) only 1 MEN1-associated tumor is required for clinical diagnosis. For a genetic diagnosis, a germline MEN1 mutation (i.e. a pathogenic variant) must be identified.

MEN1 mutations are also associated with familial isolated primary hyperparathyroidism.

The population of MEN1 patients in U.S. is likely to be around 10,000 or fewer people.

Here is a second example of MEN1 twins with different phenotypes.