Wild Problems

The affairs of the heart are beyond the limits of science and rationalism.

There is a totalizing temptation among us. We like to take our tried-and-true mental toolkits put them to work on any and every problem we come across. We overextend. Nowhere is this more common, then in our tendency to turn to The Science™ to try and solve value-based or preference-based questions, such as “When, if ever, is taking a human life justified?”, “What size should our government be?”, or “Are humans more important than other animals?”. This is the problem of Maslow’s Hammer, "If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail." It can trap anyone who is not actively reflecting on his or her decision-making. However, it is possibly a bigger issue for intellectuals or those who imagine themselves intelligent, rational agents.

Fortunately, I am far from the first person to have noticed this conundrum. Generations of thinkers have puzzled over it. And people in their everyday lives make life-changing important decision. They essentially reckon with and are practitioners of an applied form of a vaunted academic discipline, moral philosophy.

Given the ubiquity of thorny questions and a public discourse rife with discussions of fancy and somewhat alien ethical frameworks like effective altruism. I though I’d pick up a recent book on the subject. I fortuitously stumbled across a book called Wild Problems: A Guide to the Decisions That Define Us by Russ Roberts, a Chicago School economist trained by Nobel laureate Gary Becker and a prolific, popular podcaster. Roberts’ book is in part inspired by the work of Adam Smith, a profound moral philosopher who is now mostly remembered as the father of modern economics. This sets up an interesting parallelism where Roberts is a trained economist wading into the waters of moral philosophy.

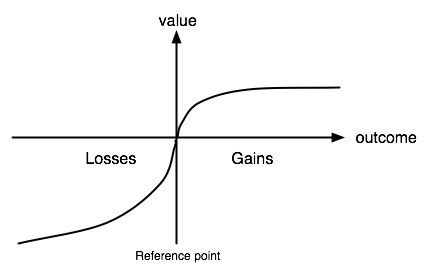

As can be guessed from the title and discussion above, wild problems are conflicts that cannot by resolved by rational analysis alone. This isn’t to say empirical and scientific questions are easy. They’re just tame. It also isn’t to say that science and rationalism can’t help resolve wild problems. In fact, these are tools that should be used to their fullest. Acknowledging the existence of wild problems is simply to realize that rational methodologies alone cannot and will not be the ultimate guide for final decisions. Attempts otherwise simply won’t provide sustainable and satisfying solutions. Values win out. Or as Hume said, “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions.”

At its core, Wild Problems is a reflective criticism of the central dogma of the Roberts’ academic discipline, economics. It’s admirable to looks at one’s cherished discipline with a critical eye, though it is maybe one of economics greatest contributions that Roberts is challenging. Broadly, it analyzes where the scientific method and utilitarian ethics (the best for the most) can resolve human problems (the tame problems) and where they fail (wild problems). The analysis is qualitative, but is still useful for readers as Roberts does outline some approaches for managing wild problems. Although I'm not sure that the work earned its book length treatment of the subject (few books do), I think it productively opens up avenues of thought that have been closed off in the minds of many young, intelligent people.

There are a number of communities, especially online, that are particularly enamored with frameworks that optimize “expected utility” in philanthropic or political settings. In non-economic speak, they essentially aim to extend the approaches of utilitarianism, rationalism, and quantitative analysis to answer ethical and political questions in ways that maximize the amount of good done. They’re the moral scientists, and they’re here to help. This tendency runs through groups like practical liberal technocrats (e.g. Cass Sunstein) to idealistic effective altruists (e.g. William MacAskill) to right-wing rationalists (e.g. Richard Hanania). Roberts is targeting his message at folks like this, and asking them to exercise a bit more epistemic humility and to think more expansively about their values and principles along with those of others. It is a gentle critique, which suites Roberts’ curiosity-first persona well.

I would have liked to see Roberts criticize many existing decision frameworks in greater detail and assemble a more robust decision framework for wild problems. This probably would have made the book less accessible, but it would have been more satisfying that a few heuristics and general guidance. Maybe this is the best that one can offer as guidance for wild problems, but it does feel somewhat insubstantial. This desire probably seems to resist the message of the book, but I think it is necessitated by Roberts' rhetorical choices. He tries to make most of his claims in a value neutral way so as to accommodate a broader audience. Vague hints of Roberts' natalism and traditionalism bleed through occasionally, but the work would have been improved by a full-throated defense of what a minimal conception of the Good should contain even if couched as his particular vision. Plus, Roberts could further caveat this argument by acknowledging that conceptions of the Good vary substantially among people. Simply outlining his core principles would helpfully orient his claims for readers. As a frequent listener to his podcast EconTalk, I have a good idea of what Roberts believes but putting it to page would have enriched this particular argument.

Containing Effective Altruism (EA)

Of late, the ideas of effective altruism or EA, as it is commonly referred to, have somewhat entered the mainstream or at least penetrated elite public discourse completely. Part of this was the intense media push around What We Owe the Future by William MacAskill, which was published a couple days before Wild Problems. The basic idea of EA is to maximize the impact of altruistic efforts. For instance, one could calculate the impact of giving money to buy malaria bed nets in Africa versus giving alms to the local underclass and conclude that the former action saves more lives and thus is the more effective choice.

But how could EA be a bad thing? It sounds great in theory, especially considered in the context of our current philanthropic institutions. These places are rife with inefficiencies and infighting; the stereotype being (ex)wives of millionaires and billionaires trying to manage motley groups of solipsistic millennials and zoomers, who are willing to cynically wield woke identity politics to climb internal hierarchies. It is also clear, in many instances, that the motivations animating the leaders of these non-profit agencies are less than saintly (also frequently self-absorbed). However, taking EA too seriously seems far more dangerous than letting the status quo of philanthropy continue. And that danger results from the same logic that give EA its edge. To do moral arbitrage eventually winds its way toward making counterintuitive or repugnant decisions.1 If we take Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) at his word (although we probably shouldn’t but bear with me), all the deposits he allegedly repurposed from his customers at FTX was done in service of an earning-to-give effort inspired by EA theorists (MacAskill himself!).

Thus, I think the true power of Robert's book lies in its simple dismantling of th memes Ea and scientism. It’s a subtle reassertion of the unbridgeable is/ought gap so astutely identified by Adam Smith’s buddy David Hume. And though it was probably more the SBF-FTX scandal that discredited EA in the last couple years, Roberts’ calm and optimistic argument will endure as a reminder to contain the ugly risks of such alien ethics. In my view, the best way to moderate an ethical system is likely similar to the best way to constrain state power: have checks and balances.

Reflections

As mentioned above, Roberts is influenced heavily by Adam Smith, especially his underrated work The Theory of Moral Sentiments. It is interesting how resonant Smith’s work is still today. And I am glad to see, we haven’t wandered so far as to forget the wisdom demonstrated by the great thinkers before us. To have periodic reminders in book like Wild Problems is essential to keeping one’s head on straight. Now, I would have also been glad to see Roberts talk more about the ideas of Smith's best friend David Hume, but I nonetheless enjoyed the opportunity to reflect on wild problems in a general and personal way.

To play us out, Roberts will give the final words:

Life is like a book that you are writing and reading at the same time. You might have a plan for how it turns out. But for it to be a great book, it needs to be savoured and chewed and digested along the way, like a book you read that changes your life. And you have to prepare for a plot twist and maybe two or three.

Related to this point, I'd recommend Erik Hoel's "Why I am not an effective altruist," which covers the repugnance embedded in EA in greater detail.