The Progressive Case for American Power

Reviewing Shadi Hamid's new book, The Case for American Power.

Today, the world needs American power, it needs more of it—and it needs it now. But power on its own isn’t enough. The world needs American dominance, too. This mean maintaining America’s political, economic, and cultural edge over its competitors. This is not because competition itself is bad; it is because the only country that comes close to competing with the United States is a brutal authoritarian regime that has only grown more brutal with time.

~Shadi Hamid, The Case for American Power

If American power declines—and if such a decline is accepted without resistance—other countries will step into the void. Seen through this comparative lens, America’s dominant role, for all its very real faults, becomes more attractive. The alternative to America isn’t some morally perfect superpower of our own imagination. Such an alternative does not exist and never will.

~Shadi Hamid, The Case for American Power

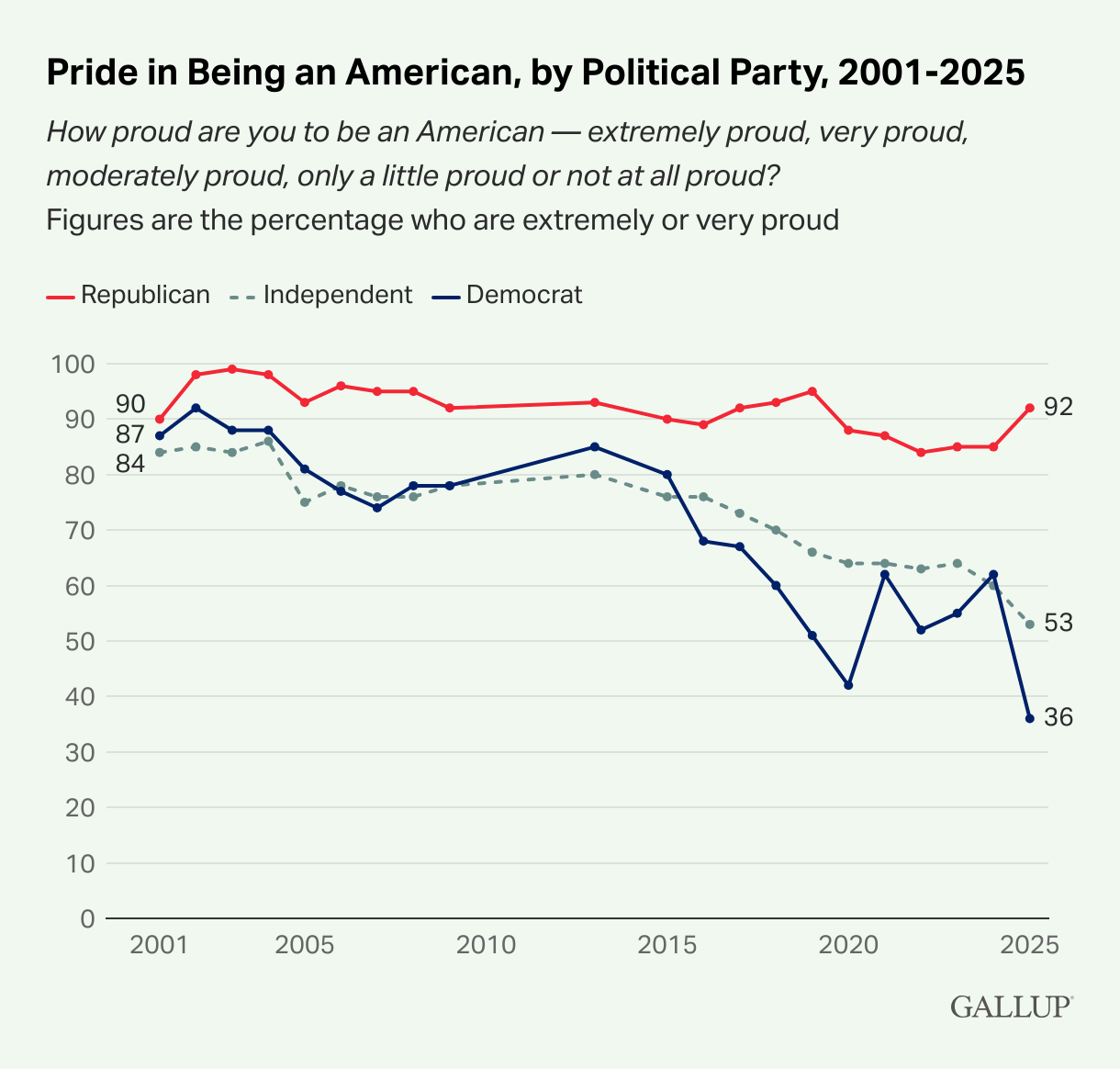

In June of this year, Gallup polled Americans about their national pride and published the results along with the past two-and-a-half decades of data on the same question. The results came back at a record-low, and the low figure was largely explained by a sharp drop in national pride reported among Democrats.

From a broad American perspective, the trend is disheartening. Why has national pride fallen so much among Democrats? Why are independent trending in a similar direction? Precise and complete answers will elude us given the data we have, but some of the story is clear. Among Democrats, reported national pride shows a sensitivity to the partisan identity of the president, especially when that president is Donald Trump. Although Democrats have always reported lower national pride in the history of survey data and there were already signs of decline prior to 2016, Trump’s first term coincided with a near 30 point erosion in national pride among Democrats. That pride showed a brief recovery during the Biden administration, only to crash even lower after Trump’s re-election in 2024.

Being able to read the tea leaves, left-liberal and progressive pundits and operatives, often motivated by a desire to keep Democrats competitive in national races, have sought to reverse this trend among their co-partisans.1 Some of the shifting vibes have resulted in genuine conversions too. Shadi Hamid can be slotted in somewhere among these left-of-center figures who are trying to find new, solid footing. Although I’m not deeply familiar with his work, his evolution appears to have really begun in the mid-2010s in the wake of the collapse of the Arab Spring, the lost promise of the Obama administration, and the twinned rise of The Great Awokening and Donald Trump. Given Hamid’s background, a scholar of Middle Eastern politics, his focus is more international than domestic politics, and, on this front, Hamid has undergone a near complete reversal from a postcolonial anti-imperialist in the vein of Noam Chomsky to a reserved champion of American power in the vein of Dean Acheson. This has culminated in a book called The Case for American Power.

At its core, The Case for American Power is a refutation of the reflexive oikophobia2 of the American left3 and a critique of its naivety about the nature and consequences of political power. It isn’t an uncritical defense of American power though. Hamid retains skepticism about some of the ways America has used its power on the world stage, especially in the Middle East, but he insists that the best and only available option for a leader of our international system is America. There are real mechanisms for reforming and improving America. He also believes that America will likely remain in the position of world leader despite the increased prevalence of narratives of American decline.

Hamid’s argument is straightforward. It has two basic components: 1) American hegemony is actually good for the world and 2) There are no superior alternatives. Hamid’s first contention rests upon both philosophical and empirical grounds. Interestingly, the philosophical premises are likely stronger or at least easier to believe in, while the available historical datasets are inherently limited and comparatively small, precluding high-confidence analysis of cause-and-effect and projections about the future.

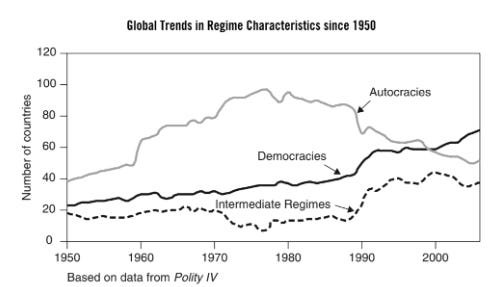

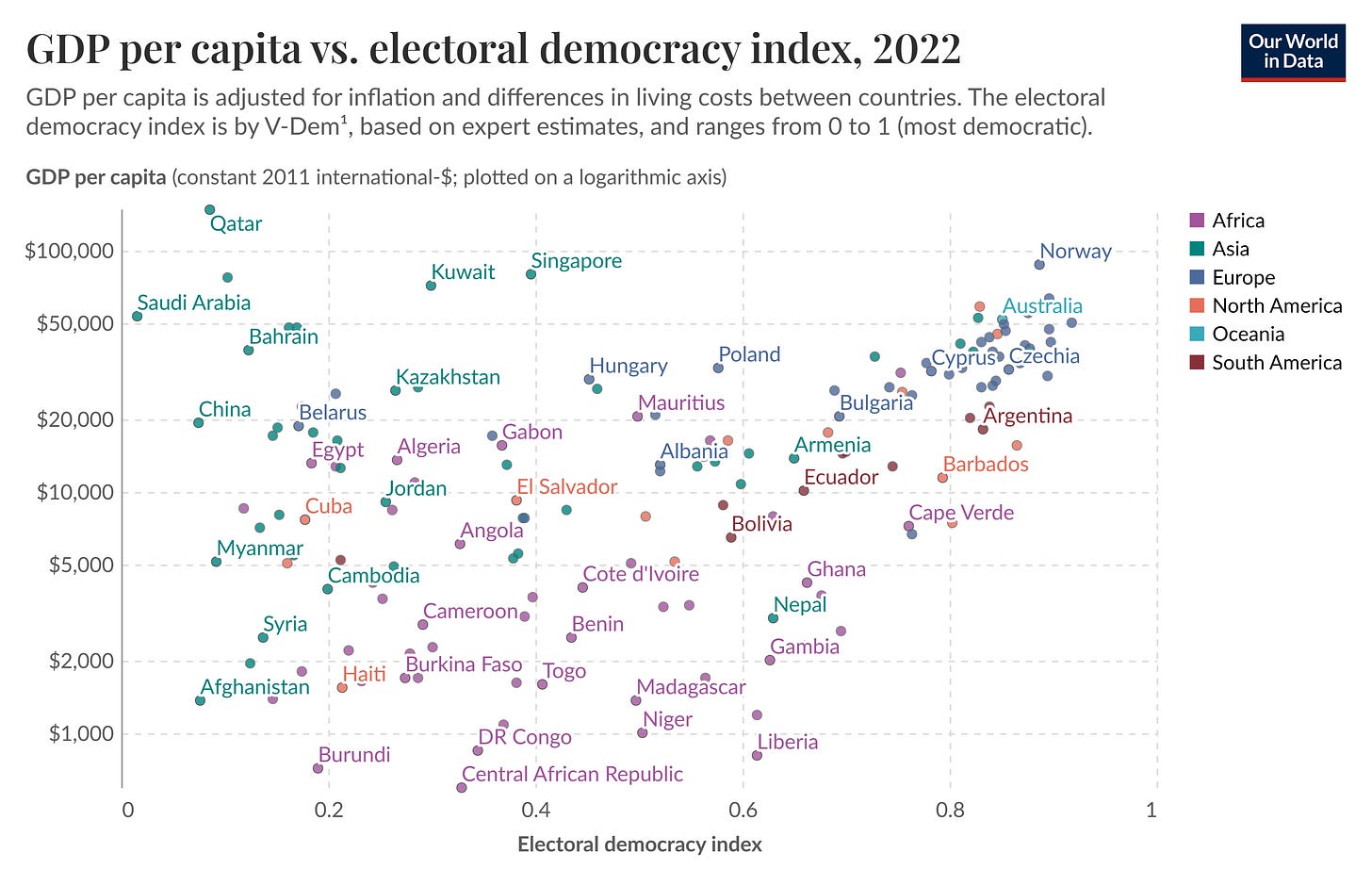

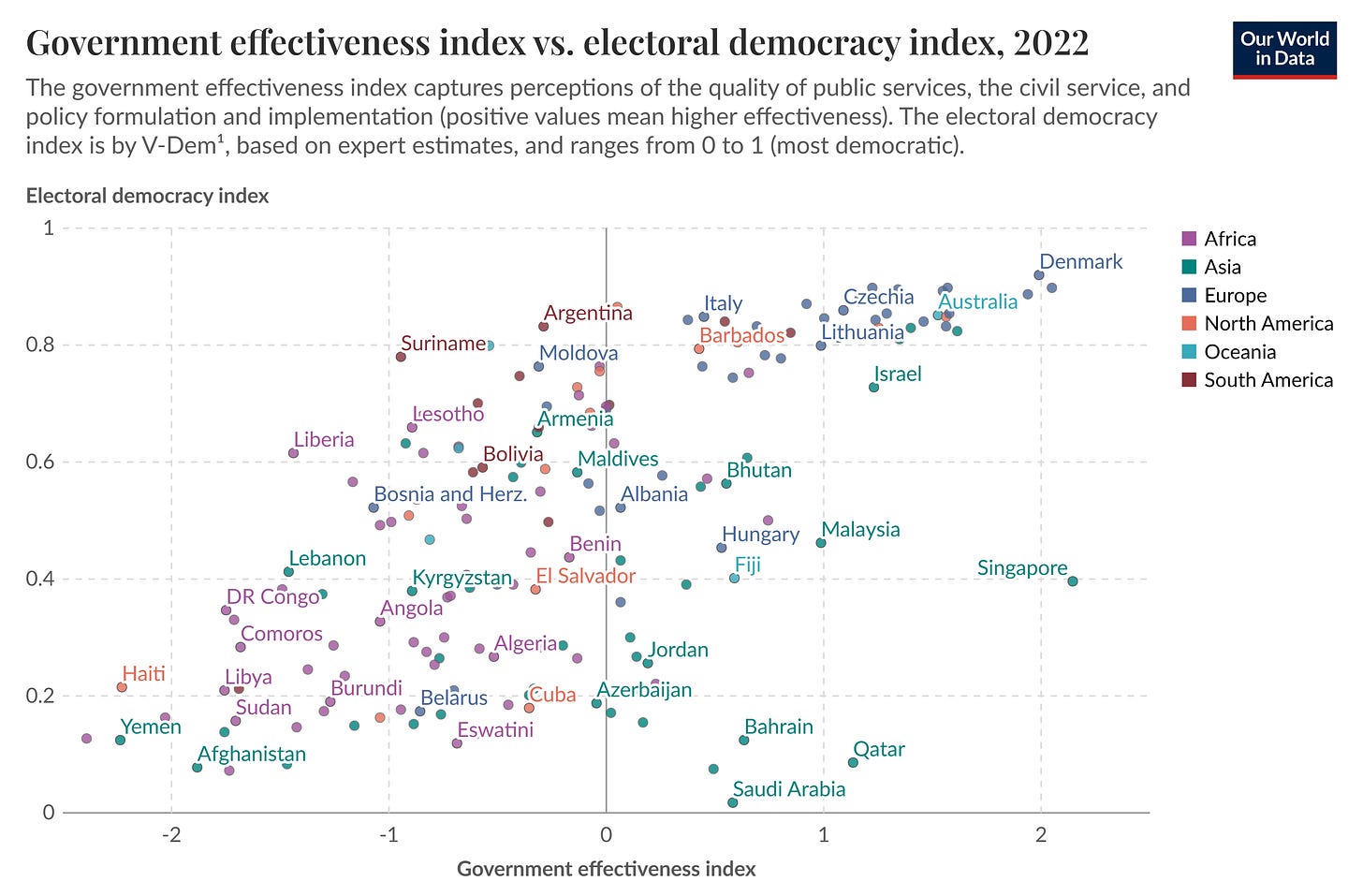

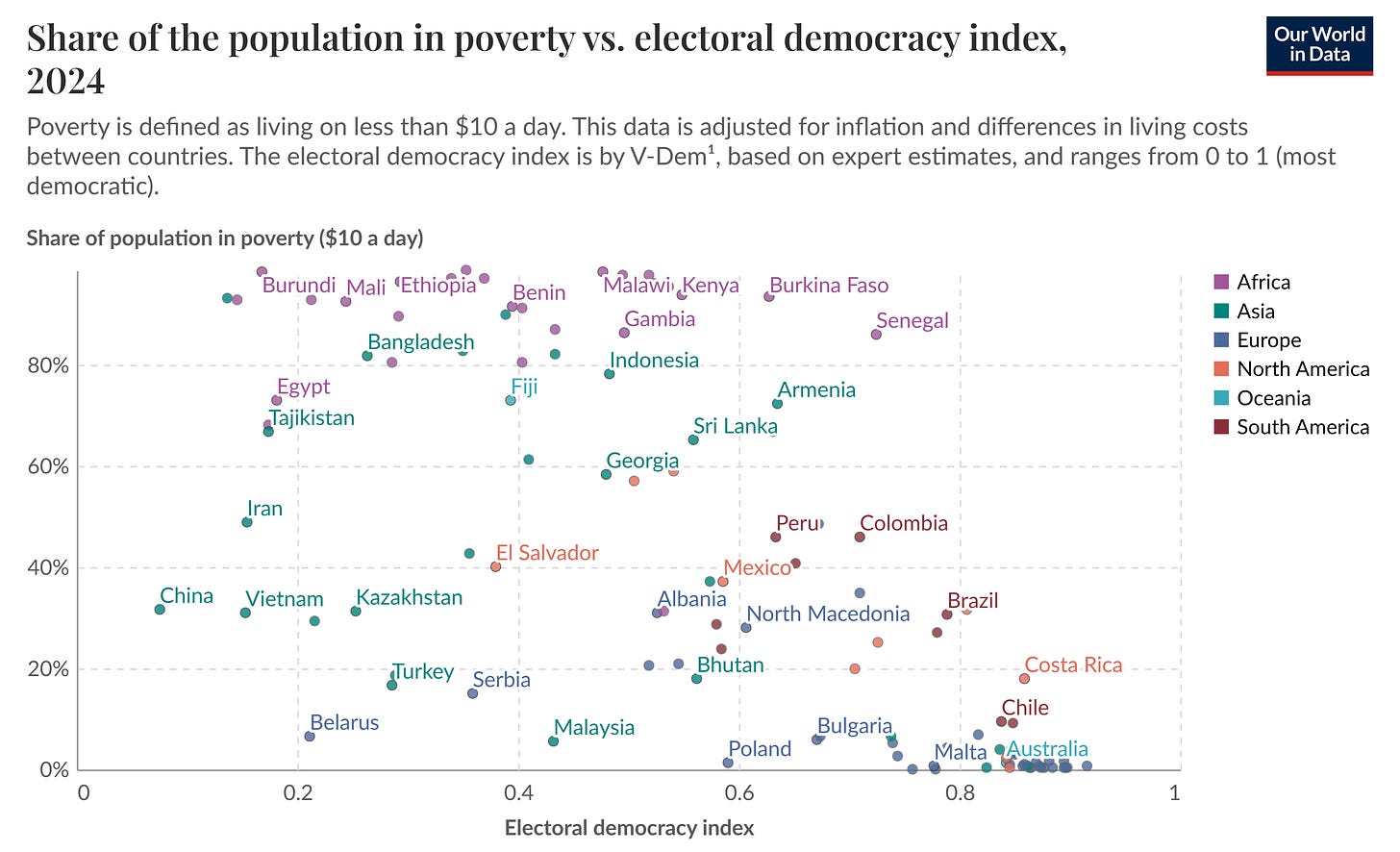

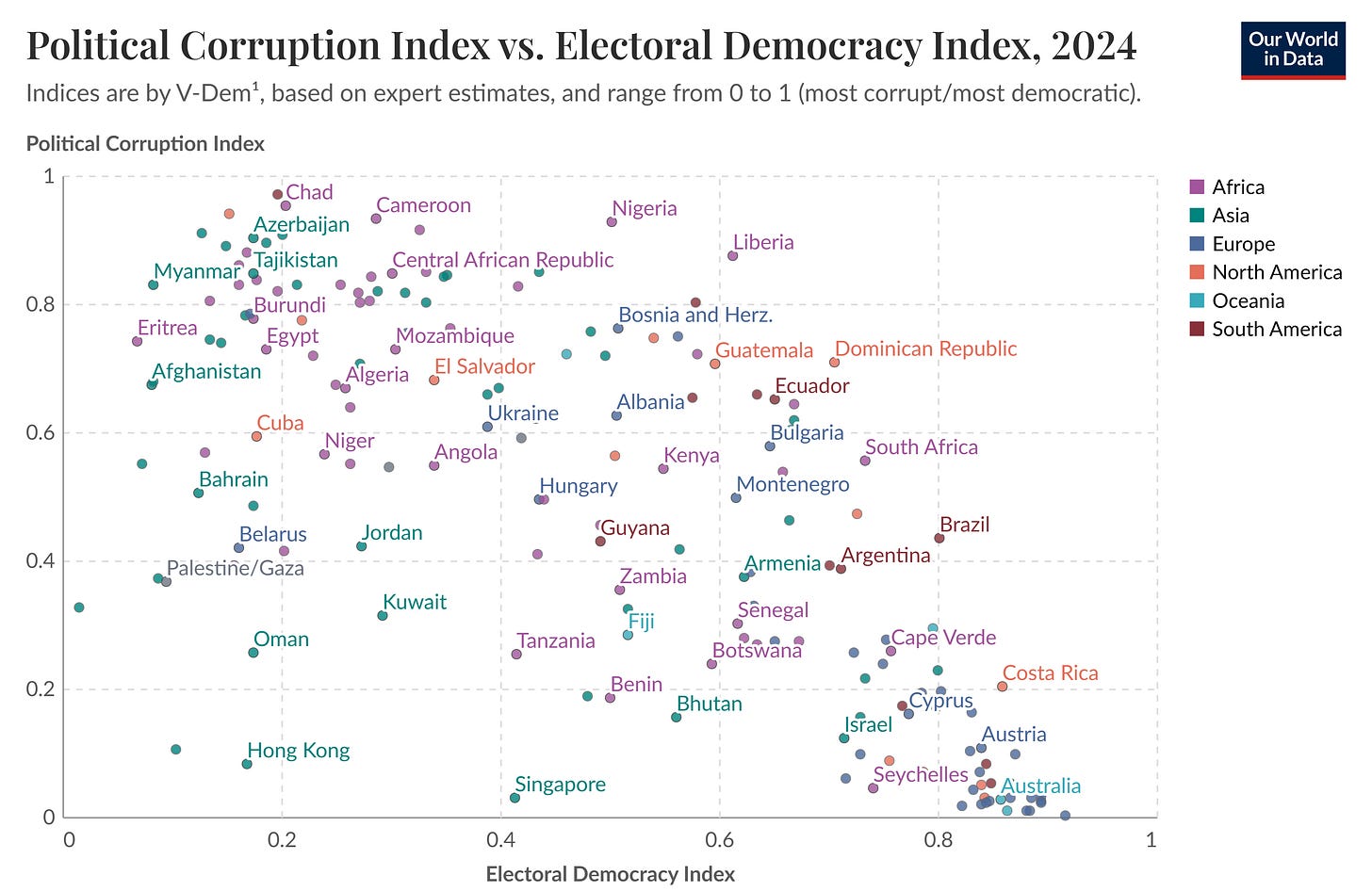

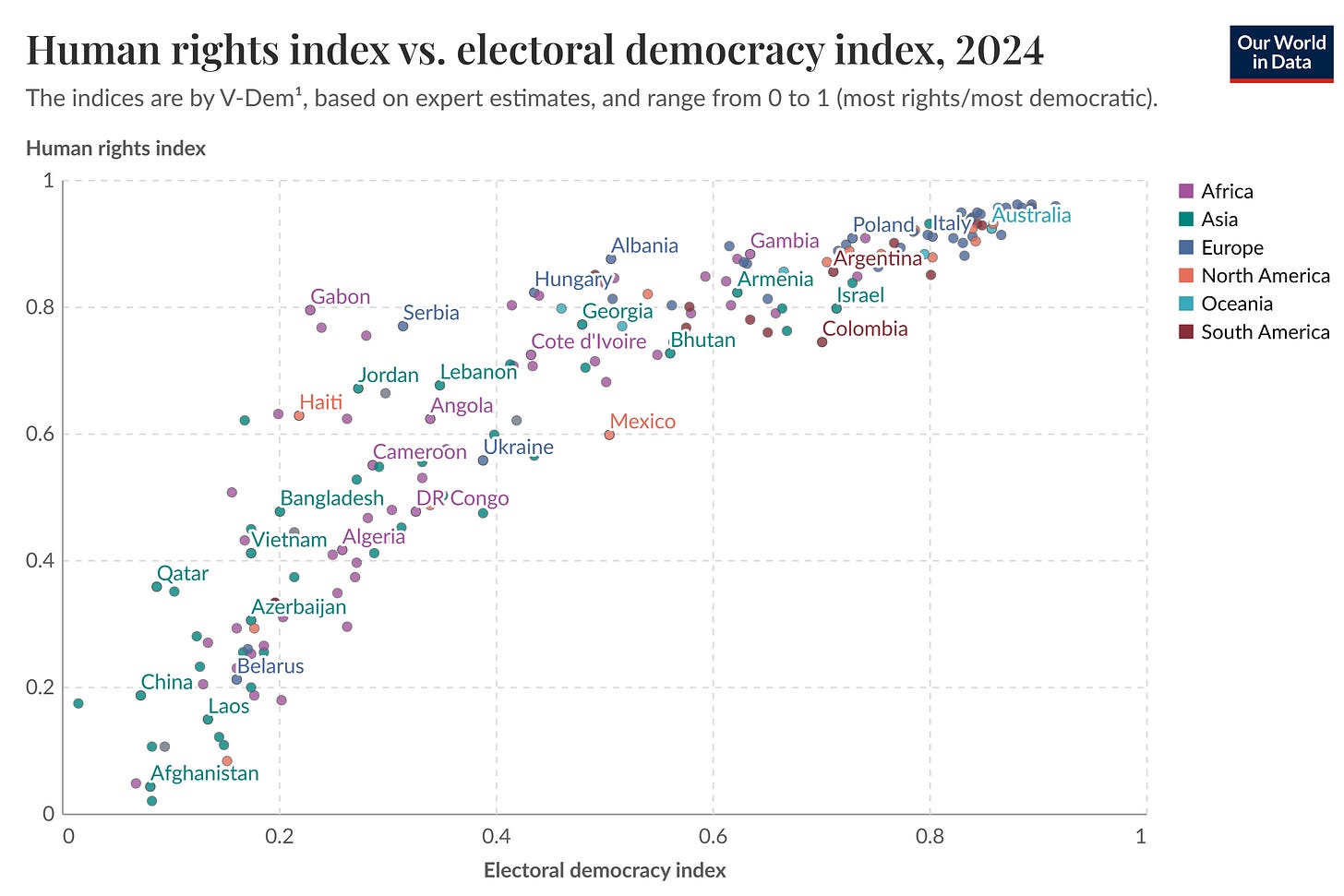

On the philosophical front, Hamid makes the persuasive yet ungainly (to many Western ears) assertion that democracy is a morally superior form of governance. Democracy embeds a mechanism of self-correction, enables the peaceful transition of power, and diffuses existential conflict. In an imperfect world of competing trade-offs, it offers a modest, sometimes chaotic, way to optimize freedom and equality for all.4 I think most readers will be inclined to demurely agree, especially if the only alternative system on offer is autocracy. However, for the potential skeptic, Hamid goes on to provide a pragmatic and empirical case for democracy arguing that democracies have historically been better at delivering peace, stability, and prosperity.5 Despite the many caveats involved with drawing causal inferences from observational, retrospective, and messy data, I think his claims are generally substantiated. Hamid’s argument, however, does overlook the cultural or institutional constraints on democracy that have historically helped it flourish, liberalism.6

On the empirical front, Hamid briefly marshals some evidence to show that Pax Americana has been a boon for the world. One prominent data point comes from a 2018 study by Aaron Clauset. Clauset observes that the rate of large wars before and after World War II (WWII)—arguably the moment of indisputable American hegemony—shows an unmistakable decline in the rate of conflict, where the incidence of large wars dropped from roughly every 3 years to every 13 years. However, Clauset’s paper also acknowledges that the sampled years prior were notably enriched with conflict and the current trend of peace could be a statistical fluke. He argues that another 100 or so years of future time is needed before we can be confident in the post-WWII liberal peace argument. Hamid omits the conclusion of the paper. I don’t raise this as a critique of Hamid. I raise it to highlight that there is a lot of uncertainty about the takeaways we should draw from the last 80 years of history. It is easy to fall into interpretations that make us look good. At any moment, our brilliant theories of how great we are can be falsified, which seems like good motivation to strive harder for greatness.

Hamid’s laudatory treatment of democracy is essential for his argument about American power on the world stage. Hamid concedes that an unchecked hegemon is likely to abuse power, but instead of another great power needing to check the hegemon, Hamid believes restraint should emerge from within. That check is America’s imperfect and contentious democracy. He insists upon this because the alternatives eligible to participate in great power competition, China and Russia, are autocracies. He spends an entire chapter cataloguing the weaknesses of autocracy, offering a refutation of arguments made about China or even Singapore figuring out how to run “smart autocracies.” He identifies two fatal weaknesses in autocratic governance: 1) They preclude organic discovery of public sentiment both among citizens themselves and between citizens and the government and 2) The dilemma of succession inherently compromises stability.

I’m less confident that certain forms of government are inherently more stable and more effective for all peoples in all contexts.7 There is substantial material, geographical, and cultural variability that likely impinges on this question. Will China be able to supplant America as world hegemon? I think it is somewhat unlikely in the short-term for a number of reasons, but I also don’t think it is inevitable that China will fail to because it is autocratic.8

The Balance of Power Alternative

Let’s take a very brief look at an alternative to Hamid’s perspective. I want to avoid spending too much time on alternative views, which of course there are many, because they’re largely beyond the scope of the book and enjoy greater popularity and prestige among Hamid’s ideological compatriots. So, I will simply provide a brief look at the strongest version of what Hamid’s argument doesn’t directly address, a “balance of power” thesis.

The main alternative to Hamid’s position of American unipolarity often comes from members of the realist school of international relations. They often argue that a single global hegemon makes for an unstable world, and many already argue that American hegemony has ended. The realist view is informed by the belief that nations will act ruthlessly in their self-interest and naturally pursue power. Subsequently, the realists only see a stable international system sustained by power sharing or a balance of power, ideally between two main power centers. The two power centers could police smaller players in their spheres of influence while checking and restraining each other on the broader world stage given that their interests would be easy to understand and coordinate around. In some ways, this is an extension of Enlightenment political philosophy, features of which have been constitutionally built into American governance. These ideas have long been championed by famous figures like Henry Kissinger.

The problem with this form of realism is that it appears to assume national interest is both discoverable and rational and that governments can effectively and coherently act upon these interests. Any examination of the history of great power conflict or American foreign policy would strongly militate against such beliefs. Instead, an examination of historical follies would likely underscore Hamid’s point concerning the weaknesses of autocracy and the strength of democracy when it comes to governing legitimacy and mechanisms for assessing the government’s gaining legitimacy, maintaining stability, and promoting prosperity. Unfortunately, I fear theoretical models and the lessons of history will be insufficient guides to the future of great power conflict. Unpredictable things will undoubtedly occur.

The Seductive Trap of Declinism

Hamid only indirectly addresses the “balance of power” alternative, which comes through his adversarial engagement with the popularity of narratives of American decline. He does offhandedly reject the idea that a multipolar world is emerging, but this never comes up again in the book outside of the introduction.9 On the question of whether American empire is itself in decline, Hamid somewhat demurs from an empirical refutation and opts to cast belief in decline as a comforting, fatalistic trap ensnaring too many Americans.10

He traces a brief history of notorious prophets of Western decline, starting with Oswald Spengler and then moving to James Burnham and finally to Christopher Lasch. By the 1970s, Hamid argues Americans had inherited a penchant for decline due to a mixture of cultural forces and basic psychological defaults (i.e. threat sensitivity, loss aversion, etc). Our healthy tendency for self-critique devolved into self-contempt, nurturing a “pessimism that discounts [our] own society while elevating less familiar societies.” Hamid really emphasizes the psychological appeal of decline:

Decline is, more than anything else, a feeling. If you think that the past was great, you’re more likely to believe that the present is worse. These feelings are subjective things. Declinism, the state of fear and fretting in which decline seems inevitable, has been something of a national past time, with each generation of Americans rediscovering what it means to lose faith.

And he relies on the claim that our attachment to stories and subjective states of mind have been common throughout history, and that even if history can be rightly modeled as cyclical rises and falls that our beliefs are not necessarily attached to the reality of our location in that cycle. In fact, our beliefs themselves may play a causal role in where we are and where we go, a dangerous self-fulfilling prophecy.

Hamid, A Champion of American Hypocrisy

No one is wearing a mask because it is no longer possible to see what there is to mask.

~David Runciman, Political Hypocrisy

Perhaps the most intriguing part of the book is Hamid’s chapter-long defense of American hypocrisy. It is very much along the proverbial lines of “hypocrisy is the tribute vice plays to virtue,” where Hamid accepts America’s expressed idealism as genuine are compromised by the tragic limitations of reality, which inevitably generate actions inconsistent with heartfelt values. Hamid stresses over and over that the world is brutal and that the use of power is inherently sullying but the burden must be born. America is the right choice because it is exceptional in that it is the one powerful nation organized by ideas. We often fail to live up to our ideals in practice, but at least we’re trying.

This is, of course, a revolting sentiment to those in the postcolonial or Chomskyite traditions. To them, American ideals are a veneer painted upon ugly power plays and sinister conspiracies executed by special-interest and political elites so as to dupe brainwashed members of the broader American public. The litany is long and includes American support for right-wing dictators in Latin America and the Middle East, covert action to topple democratically elected socialists and communists abroad, and exploitation of the resources and people of the Global South.

Hamid, both literally and figuratively, holds trump cards against the anti-imperialist left’s criticism of American hypocrisy. First, he recounts how Barack Obama’s unimpeachable postcolonial credentials, including close personal connections with pro-Palestine figures like Edward Said and Rashid Khalidi, failed to deliver significant change in U.S. foreign policy towards Israel, showing that intentions and outcomes can diverge for many reasons. Second, he trots out Donald Trump as an example of a less hypocritical version of American foreign policy. Trump forgoes paying deference to American idealism and just acts in whatever way he sees fit. This is meant to contrast, for Hamid’s intended left-of-center audience, how some amount of hypocrisy can be preferential to none. Additionally, Hamid also draws attention to the hypocrisy of many on the anti-imperialist left, highlighting how little they have had to say about Russian imperialism in Ukraine and how they have ignored how many eastern European countries voluntarily sought alliance with America as a bulwark against Russia.11 Hamid goes so far as to assert, “So many anti-war voices are not, in fact, anti-war at all; they are anti-American war.”

A Verdict on the Progressive Case for American Power

To be sure (a phrase Hamid, like many political writers, loves), Hamid presents a reasonable argument for America, the benevolent hegemon. However, the argument is more of an attempt to move sentiment among Americans, especially left-of-center Americans, than an attempt to actually analyze the state of American power and the current dynamics of great power politics. Thus, I’m judging it as a rhetorical object. And I do think it is necessary to make this popular case against self-destructive manifestations of oikophobia or self-loathing because they probably have warped our politics for the worse, having long ensnared academics and activists on the left and currently gained purchase among some of the paleoconservatives who staff Trump’s administration and run intellectual periodicals.

Insofar as Hamid is speaking to those to his left, it behooves his argument to avoid a rah-rah tone, meaning the praise for America is never delivered in an entirely unqualified or unconscious fashion. The strongly pro-American argument is consistently positioned against the common left-wing criticisms of American foreign policy and accompanied by an acute awareness of the stigma attached to unreflective patriotism. Nonetheless, the fact that Hamid is willing to regularly profess a love for both the idea of America and the America he lives in today is something I greatly appreciate. It appears genuinely felt. I hope Hamid’s sentiments are contagious among his co-partisans.

Now, it can simply be exciting to see this sentiment at all.12 And yes, I’m excited to see a left-of-center Muslim political figure come around to this position, a position that many former liberals and left-wingers have come around to again and again in the wake of the world wars, the rise of the Soviet Union, and the anti-war agitations of the New Left.13 However, the message is somewhat marred by Hamid’s residual ambivalence. Hamid is deeply troubled by the recent conflict between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, and he sees that conflict, which has for now been resolved, as a deep threat to the thesis of his book. However, I fear his read on those events is blinkered my his own particularism—commitments to an ethnic-religious group identity which themselves are often understood as inconsistent with or in tension with the liberalism of America.14 Understandably, it is difficult to decouple from such intimate commitments in order to favor more abstract ideas. In fact, I was actually surprised that Hamid struck a more sober tone on the subject than he has sometimes done when commenting more extemporaneously.

Altogether, I agree with the broad version of Hamid’s argument. I, too, think power must inevitably be used in world affairs. I, too, think America is the best available option to be trusted with that power. I, too, believe that Pax Americana has been salutary for the world. I, too, think we should work to preserve and extend American power. But, I’m not sure these beliefs can be accurately labeled as “progressive” despite how I’ve framed this review. Nonetheless, Hamid does clearly believe that progress is a political choice, and it’s one that the American electorate is capable of making together.15 This suggests a profound trust in Americans, which is a bit surprising from someone on the left-of-center in the wake of Donald Trump’s re-election. Admirably, Hamid has taken the long view. Let’s pray he’s right about American resilience and that his co-partisans start similar journeys back to a faith in the American project and optimism about its future.

We’ll end with some final commentary from Hamid on American power:

When American power seemed uncontested after the Cold War, a growing number of Americans could afford to imagine a world with less of it. It was peacetime. The United States had no real competitors, and political elites in Western democracies took for granted their own permanence. Around the globe, Americans saw more friends than enemies, but even our enemies—weak as they were—could be transformed into friends. Or so the thinking went. Those easy assumptions are now lost to history.

Perhaps the center of this recent effort, or at least the most visible version of it, has been Ezra Klein’s podcast at The New York Times. However, Klein is characteristically late to the party, having, like many elite liberal pundits, tried to surf the crests and troughs of cultural vibes without really having to really change anything fundamentally. Before the “vibe-shift” was impossible to ignore, there was already a proliferation of philosophical and political projects let by varied sets of heterodox figures with substantial followings in new media venues like Substack or YouTube. This even included different generations of heterodoxy (remember the Intellectual Dark Web, anyone?), which found much greater purchase on the political right before the political left started feeling the pull too. Now, the distinction between what is right-wing versus what is left-wing is breaking down more along the lines of establishmentarian and populists.

Hamid borrows the term oikophobia from the conservative British philosopher Roger Scruton. It is defined as “the fear or hatred of home or one’s own society.” Hamid points out that oikophobia “tends to afflict those with the luxury of taking their own good fortune for granted,” associating it with Americans of higher social status, affluence, and educational attainment—all sociological characteristics increasingly common among those identified as progressives in America.

Oikophobia is most common among the academic left, having a tradition that is usually traced back to Edward Said’s Orientalism and often runs under the label of “postcolonial studies.” It is a tradition that was nurtured and expanded by many celebrity scholars including Frantz Fanon, Jean-Paul Sartre, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Homi Kharshedji Bhabha, and most famously Noam Chomsky. There are also academics from the field of international relations (IR) theory who often identify with the label Realist that share similar worldviews. This includes figures like John Mearsheimer. There is a complementary phenomenon on the American Right including foreign policy thinkers who identify as “restrainers” or who are sometime pejoratively labeled “isolationists.”

Hamid implicitly presents an alternative and more modest claim that democracy is more consistent with the social constraints created by human nature. It is interesting that he doesn’t extend this understanding of competitive interpersonal dynamics within a polity to those that exist among nations. Maybe he does? It is not an analytical perspective he presents and may be inconsistent with his implicit rejection of the “balance of power” theory of international relations in favor of American hegemony. In many ways, Hamid is arguably restating aspects of Francis Fukuyama’s “End of History” thesis and saying all the hopes of liberal democracy reside in America’s belief in itself.

Hamid borrows most of his empirical argument for the effects of democracy from Morton H. Halperin and his co-authored book The Democracy Advantage. Here’s an example of Halperin’s work accessible for free.

It is interesting to me that Hamid rarely pair “liberal” and “democracy” in his argument and liberalism figures less prominently in his defense of American power than democracy. However, it is really the principles of liberalism constraining democracy that have makes America distinct. This is an important unexplored dimension especially considering Hamid’s work on democracy in the Middle East. Most of the democratic outcomes there are unlikely to be accompanied by a flourishing of liberalism.

This is probably an unfair rejoinder to Hamid’s claims since this isn’t exactly what he’s claiming, but I do think he is being a bit too sanguine about democracy.

There are other considerations too, such as in a world with a dominant China, would China actually care to play the role America has or will it retain its greater focus on domestic affairs and affairs in its backyard.

I haven’t seen Tooze bros respond to Hamid arguments here yet, but I’m sure they’ll be unhappy about it.

Outside of the chapter on decline, Hamid does present some data that indicate that claims of American decline are overwrought. This includes pointing out that the US economy has roughly doubled in the years since the financial crisis while the Eurozone has stagnated. There are of course many responsive criticisms to assertions of America’s economic might. This debate is beyond the scope of the book.

This is an indirect critique of the neorealist argument from figures like John Mearsheimer that NATO expansion eastward provoked Russian invasion of Ukraine.

There is a similar phenomenon when it comes to black Americans or women openly embracing conservative talking points. There are some dangers to simply rewarding mainstream political views simply because they’re expressed by a speaker with a particular identity. Doing this, to some extent, is a tacit embrace of standpoint epistemology, which is otherwise at odds with the dominant epistemology of an open (aka liberal) society.

This is an oblique references to the politicos who are often referred to as neoconservatives, though this label is inaccurate as Jonah Goldberg has written and spoken about many times.

Hamid’s relationship with the political philosophy of liberalism, which is what I’m referring to here rather than the ideology of most Americans who identify themselves as liberals, is fraught. It is the subject he returns to on his podcast Wisdom of Crowds. Admittedly, Hamid struggles to sometimes reconcile his sincere commitment to his faith (Islam) with the principles of liberalism: individualism, egalitarianism, universalism, and meliorism.

We don’t know exactly where Hamid would like that progress to go as it is not explicitly addressed.

I also wonder if there disgust is tied up in it all. Like, a desire for purity that makes people lose their Brooklin accents or protest something morally repugnant over something more fundamentally problematic close-to-home. A thing I face in my community is a ton of (admittedly youthful) energy over Israel-Palestine while there are large numbers of homeless all around. Perhaps this is another facet of extremety: youth.

Love this!