Killing Mendel

Heroes live forever, but legends never die.

This piece is unfortunately not a history of science essay on Gregor Mendel. I have little special to add on that subject at this time. If you are looking for something like that I recommend the “Flowers He Loved” section (pages 47-55) of The Gene by Siddhartha Mukherjee. I also recommend reading Niko McCarthy’s “Gregor Mendel’s Vanishing Act” here at Substack. Herein, I’m venting my spleen about the a dead-end idea that has a hold of a small number of impassioned academics. They stumbled into a strange argument, the teaching and celebration of Mendel is making people believe in race realism and thus its teaching must be abolished. I honestly think their arguments are not likely to go anywhere, but nonetheless I felt compelled to complain about it.

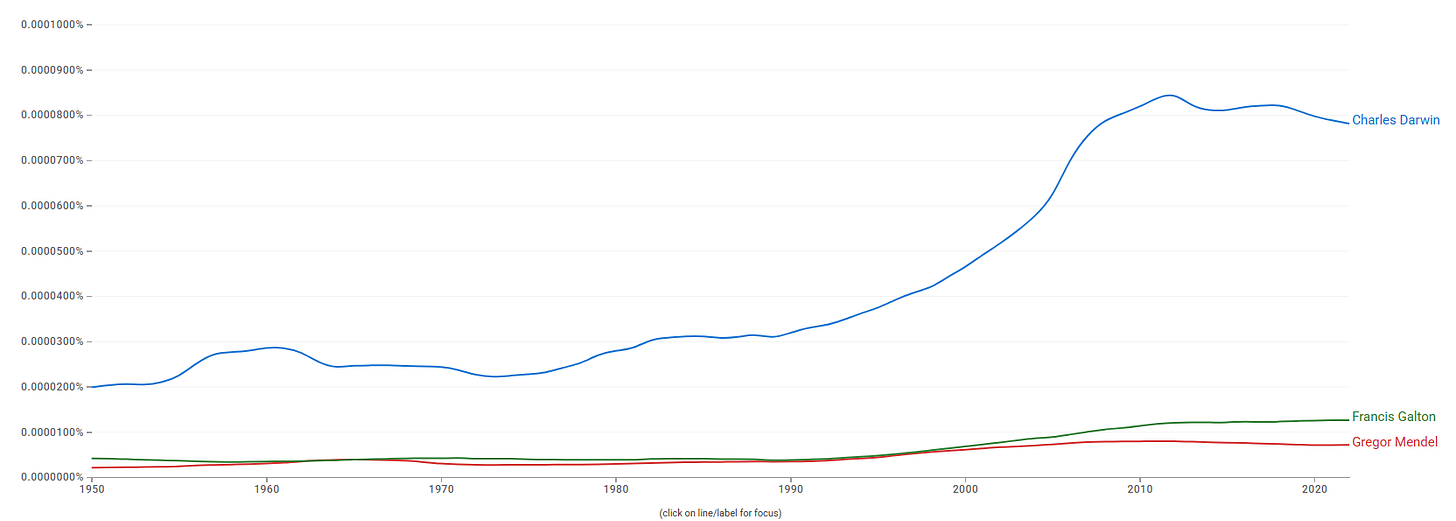

For almost a century now, the Pisum sativum breeding experiments carried out by a 19th century Austrian monk have been taught as the foundation of the science of genetics. Subsequently, this monk, Gregor Mendel of course, has become a bit of a mascot for both the field and possibly biological sciences writ large. It may be more accurate to say he’s Robin to Charles Darwin’s Batman. But aren’t such attempts to precisely taxonomize the current cultural statuses of past intellectual giants foolish? It’s part of the reason I’m having to write this piece. Anyway, we do know that without this dynamic duo, the modern synthesis, the marriage of evolution and the science of heredity, would have been greatly delayed (see the meme below).1 Like all ideas that precede their time, Mendel’s research languished in the dustbin of history awhile until 20th century geneticists re-discovered him at an hour of great need. Despite Mendel’s obvious contributions, some scientists are now eager to dispense with him. I protest. How rude!

To some modern priests of genetics, Mendel’s theory has become a heresy. They believe the teaching of a simplified model whereby the inheritance of a binary trait is predominantly (or wholly) influenced by the allelic status of a single gene encourages belief in “unscientific notions of genetic essentialism.”2 More specifically, these priests are worried that Mendelian genetics reifies race as a biological phenomenon rather than a social construct.3 Their worries extend to a nightmare scenario where misinformed extrapolations of Mendel’s pea plant experiments animate or excuse systematic forms of discrimination. Concerns about eugenics and racism (and by association Nazism) are quite a specter to invoke in association with Mendel. Oh, the price of fame!

These concerns also strike a note of unintentional irony. If we peer into the early history of the parallel tradition of quantitative/statistical genetics, then it is clear its associations with the Stygian evils of eugenics are quite a bit closer.4 Should we simply abolish the field entirely? In fact, the Pater familias of this lineage of genetic thought crime was none other than Darwin’s half-cousin, Francis Galton, who got - let’s say - a bit overeager with applying Charles’ theory. Incidentally, Galton is also the father of foundational statistical concepts like correlation and regression to the mean. Awkward, indeed. Let’s just say, scientists, by necessity, came around to separating the art from the artist well before literary critics.5

Social Attitudes Are Independent of Genetics Education

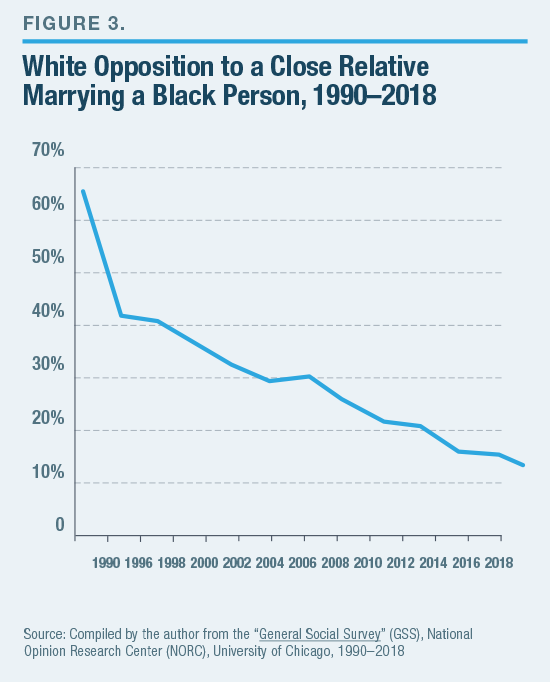

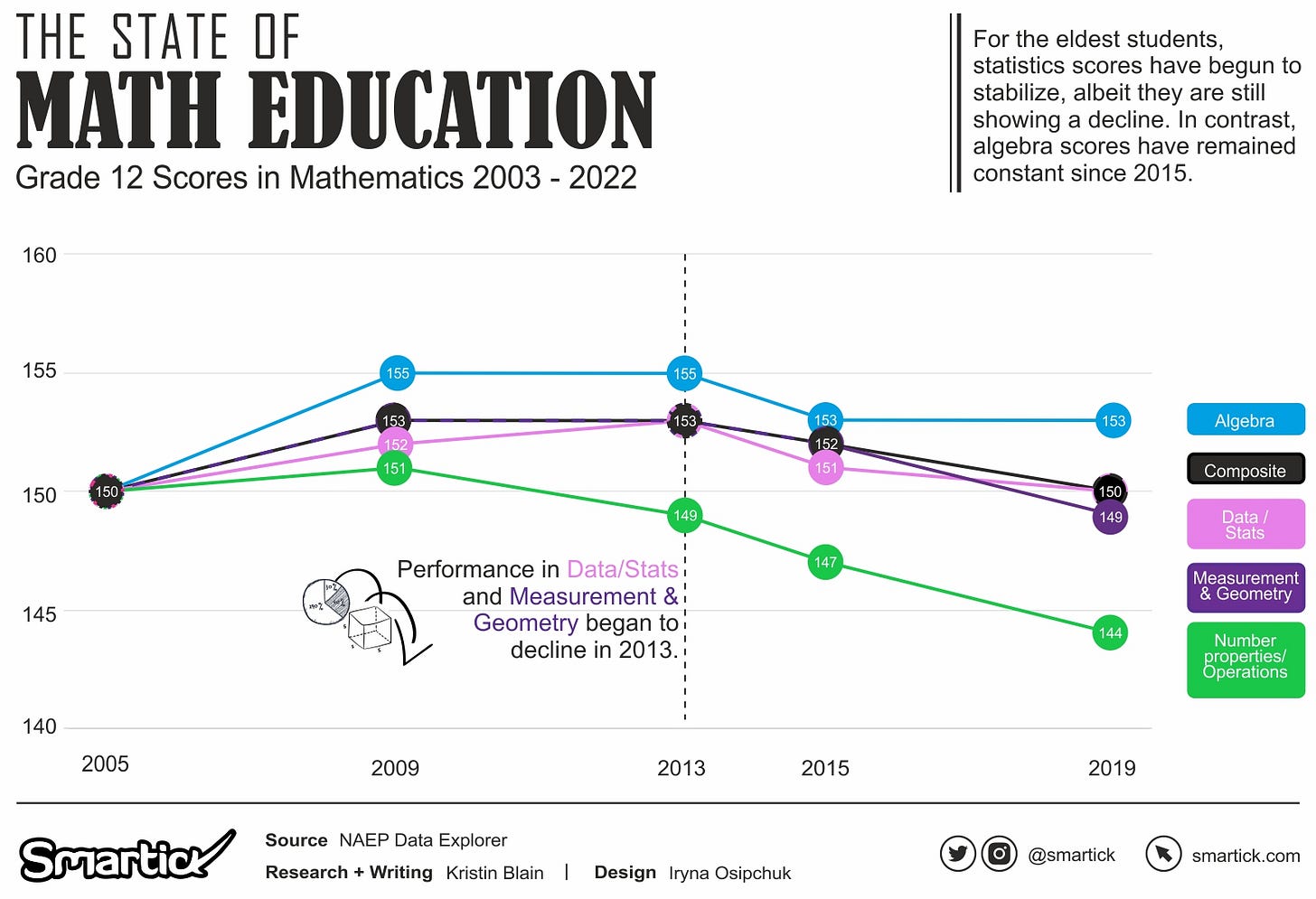

Let’s set this irony and uncomfortable history to the side and think broadly about trends in social attitudes concerning race with respect to the largely unchanged practices concerning basic genetics pedagogy. If Mendelian genetics education seeds young minds with essentialist misconceptions about race, why has a growing public consciousness of genetics (i.e. the Human Genome project, direct-to-consumer ancestry testing, Angelina Jolie and BRCA testing, etc) and possibly increased knowledge of genetics generally coincided with a dramatic liberalization of racial attitudes? Even if we just look at our recent era, we can see social attitudes have continued to liberalize regardless of whatever the high school biology teachers have been saying in their classrooms (see an example below). If we believe these are legitimate trends - something very uncontroversial to believe - then even if it were somehow true that teaching Mendelian genetics increased essentialist beliefs, where exactly is the harm that we can attribute to it? Isn’t it simply being overwhelmed by other social forces?

Maybe it is unfair to parade this progress on racial attitudes before the anti-Mendel brigade. There are certainly a number of possible rejoinders. They would likely argue the progress observed in social survey data (like shown above) are largely a function of social desirability bias rather than authentically held and acted upon beliefs. These objections would probably come with the usual references to the various well-known and well-described social and material disparities that have stubbornly persisted between blacks and whites in post-Civil Rights era America. They would also likely argue that the pedagogical concerns are truly about teaching genetics accurately, and its just that on the margins that it also happens to be beneficial for racial attitudes. This is the motte to their bailey. Because it is indeed true that most human traits of social interest, like height or intelligence (which themselves are likely to function differently to some extent), are under the partial though meaningful influence of an enormous number of genetic variants and as traits vary continuously. Given this, it should also be clear that the genetic contribution itself is not independent of other influences. There can be and often are interactions between genes and the environment, the environment may even override the impact of genes on a given trait, or even a trait that looks to be under genetic influence may simply look that way because of environmental effects that piggyback on the genes for unrelated reasons. It has also often been argued by some geneticists like Kevin Mitchell that development itself is a source of phenotypic noise.

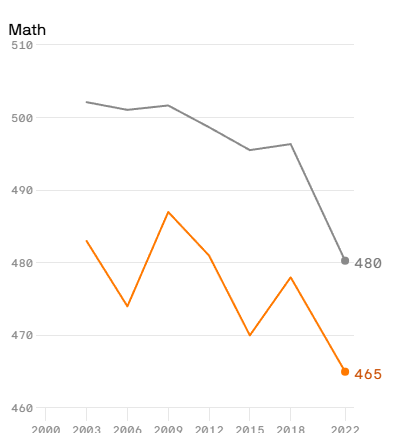

Nonetheless, the complexities and subtleties of active and open questions in genetics are usually not the purview of high school teachers and students. Additionally, many students are not prepared with the prerequisite knowledge to embark on a more sophisticated genetics curriculum (see figures on U.S. math competency below), and it is likely that leaving Mendelian genetics out entirely would create more harm than benefit. Although most everyday traits are complex in nature, any given individual has a high probability of interacting with genetic test results. Most of the clinical genetic tests and working medical geneticists still operate under Mendelian assumptions.6 Single-gene conditions are rare in isolation, but somewhat common in the aggregate (see my Substack Note on the number of people affected by rare disease versus those who innately have blonde hair). Genetic concepts like epistasis, linkage, penetrance, and expressivity are often easier to grasp when a foundation of Mendelian genetics has been established. This is how the curriculum is already designed - just crack open most genetics textbooks.

To conclude the interlude on social trends and education, I’d merely like to point out that we would probably do well to show a greater deference to the things that appear to be working just fine and be less eager to go in a tinker with them.7 There are bigger fish to fry, such as actually improving the rigor of the curriculum wholesale, including of those foundational statistical concepts mentioned before. Regardless of how noble and admirable the intentions of any would-be reformer, the desire to use education as a tool of social engineering is a great way to create political opponents and possibly degrade the social credibility of institutional science. Unfortunately, science has already incurred significant costs on this front.8 The tragic reality is that even the most sincere of beliefs can’t rearrange the material world. And even if we eliminate every trace of discrimination and racism from the world today, differences and disparities would continue. Further, even if we somehow could rebalance these differences and disparities, new ones would emerge as events unfold.9

What Does the Evidence Say?

Before I take a brief look at some data on this question, I’d like to point out the stark differences in rigor, replication, and validation between Mendelian genetics and alternative theories of genetics instruction.10 Mendel performed experimental work on a somewhat easy to manipulate pea plant and based on his repeated observations inferred principles of heredity. These principles, which could be regarded as predictions, were in large measure validated for single-gene traits many years later. They’ve also weathered more than a century of new discoveries and advances. Even to this very day, these principles inform a great deal of genetics research, including linkage mapping and genome-wide association studies. Contrastingly, the anti-Mendel brigade would like us the kill Mendel because of handful of small studies that rely on self-report measures using designs that cannot actually rule out confounding factors or prove generalizability and show no durable, real-world effects. Where is their humility?

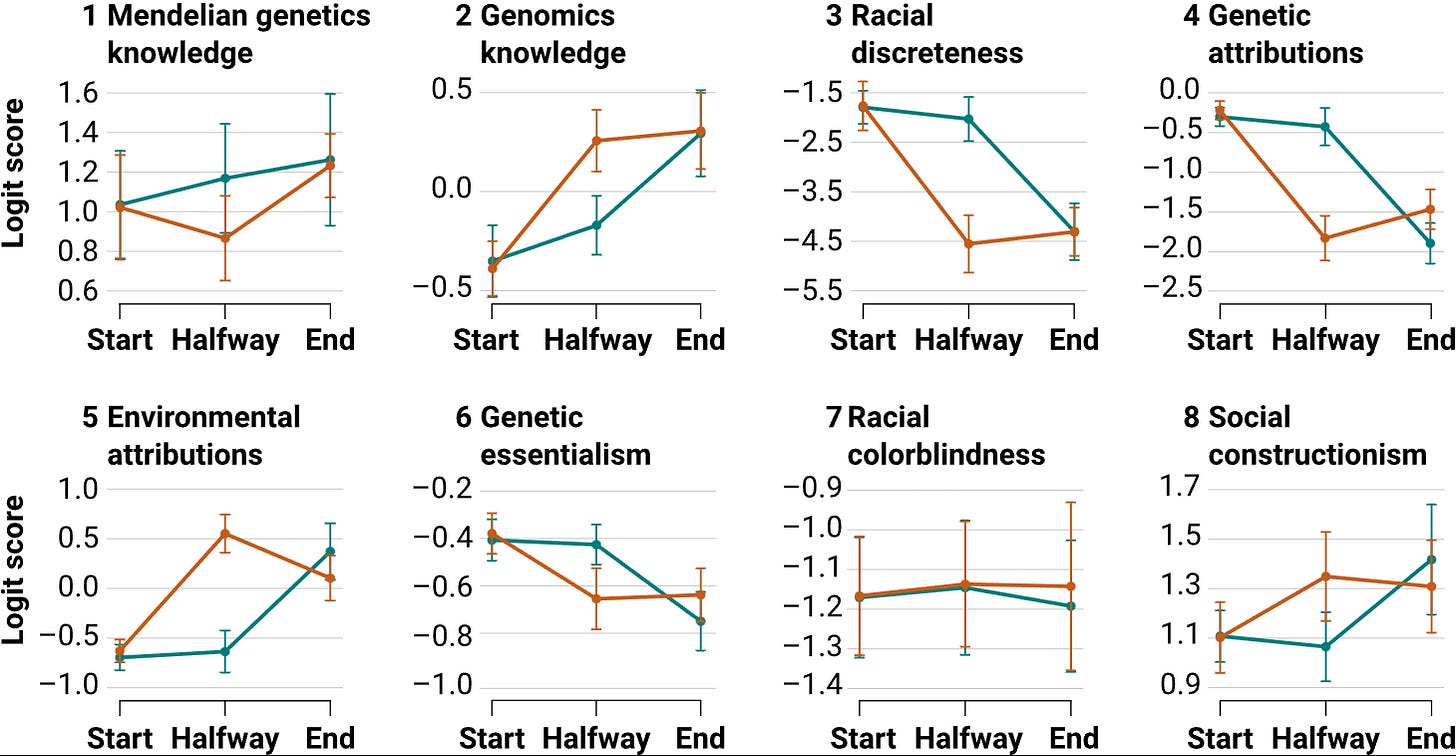

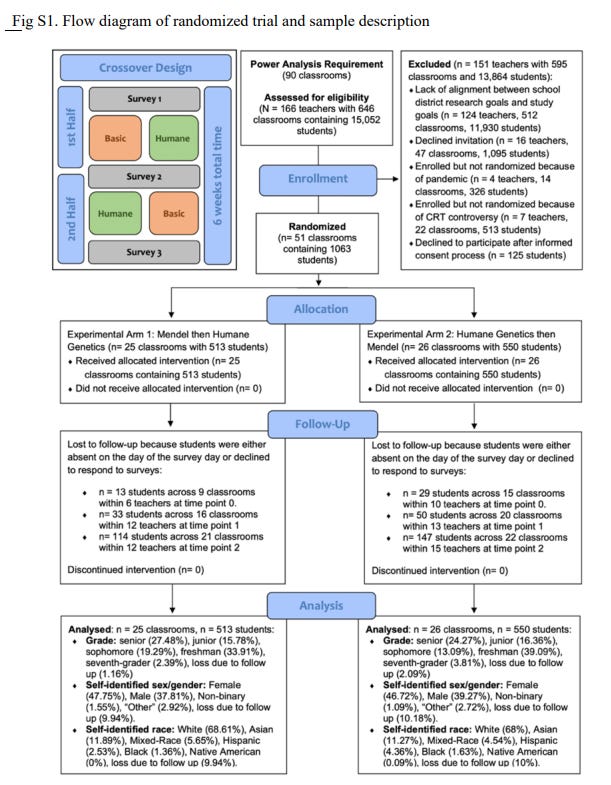

The one study that one dogged anti-Mendel advocate Kostas Kampourakis argues has “convincingly shown that replacing Mendelian genetics with a more holistic view can have very positive effects with respect to students’ understandings and preconceptions” and that it’d “be best to stop teaching Mendelian genetics in schools” is a single randomized trial using a cross-over design conducted on a sample of roughly 1000 mostly high school biology students taught by 15 teachers across six U.S. states, where the students beliefs are assessed by a survey prior to the treatment (either basic Mendelian genetics or the “Humane” alternative as genetics instruction) and then assessed again afterwards and then the different treatment group cross-over to the other type of instruction and are assessed again (see the trial design figure below). The design and details of the experiment should raise a number of concerns to any scientist familiar with evaluating research studies, especially if these are to be the studies that inform practical guidance of some kind.

First, there is the obvious fact that these data are extremely recent so there is no longitudinal follow-up. The phenomenon of washout - the effects of an educational intervention attenuating or disappearing overtime - has been well-described. Subsequently, any reasonable advocate for a change to current educational practices would benefit from bringing actual longitudinal data to the table. In this case, the work was conducted between 2019 and 2022 and was published in February of 2024. Not to mention the fact that the intervention itself was just 3-weeks of instructional time. Second, the study design has artificial constraints that will not hold in the typical classroom environment. Specifically, the study omits all instruction about differential rates of genetic disease in different ancestral populations. The authors argue this is a strength of their program, but this is silly as the reality of these differences are impossible to hide and already a fixture of general knowledge. This speaks to the propensity the study author have for hiding inconvenient findings that speak to deeper limitations in their study. For instance, they bury the finding that a greater average belief in genetic essentialism blunts the treatment effects in their supplement along with their findings on the effects of the racial composition of a classroom or the timing of instruction on their readouts.

There are some smaller weaknesses to the study that shouldn’t be overlooked either. Potential subjects were sidelined for various reasons, which means there is likely some degree of ascertainment bias in the sample. This is most likely related to the types of educators that are likely to enroll in the study, which may also be related to the types of students in those classrooms. The general racial composition of the classrooms enrolled in the study should be a bit of a giveaway about the study’s likely generalizability too. There were also differential attrition rates between the treatment arms. Arm 2 saw twice the attrition rate of Arm 1. Additionally, the number of classrooms enrolled (51) fell below the study's preregistered power analysis total of 90, a source of type II error. The power analysis is relevant because they report a small effect on beliefs in genetic essentialism (one of their three pre-registered hypotheses).

But hey, for a second, just ignore all the above methodological criticisms. The invocation of this study is self-refuting with respect to concerns about teaching Mendelian genetics. Both treatment groups end up in the same place! Regardless of which study arm we look at, they’re indistinguishable by the end of the study (see figure below). So if we just take the study as is, the actual recommendation should not be to eliminate Mendelian genetics, it would be just to add their “humane genomics instruction” on top of the current curriculum. But let’s be honest about what is really going on here, teachers are preaching to students, and those students are echoing those sermons right back. And it’s extremely unlikely, most of these students haven’t already been deeply schooled on the traditional liberal pieties regarding race. For God’s sake, this is survey data on high school and middle school students. That’s it! Do we actually have a way of accessing the deepest recesses of people’s minds and reliably predicting their behavior? No. No. No. In fact, the criticisms of the use of social genomics to predict behavior or guide social policy have the same character as my criticism here. One cannot agree with one but not the other.

Legends Never Die

To recap, Mendel’s place in the history of science and his contributions to the science of genetics endures. The actual scientific critique that his model of heredity is overly simplistic is not fatal nor new nor relevant to the impact of his contribution or the utility of teaching his model. The same argument can be made about Newtonian physics yet we continue to still see value in teaching and using Newtonian physics.

I’m extremely confident that Mendelian genetics will continue to be taught and will remain useful as the field of genetics advances. So I apologize for whining so much about this non-issue. I just can’t help that I’m annoyed. I’m annoyed that members of the scientific community are wasting their time on these questions. I’m annoyed they’re often motivated more by political questions than raw curiosity.

If you are someone who thinks I’m exaggerating, peruse the bibliographies of the authors of the study I discussed above. Ask yourself if these investigators are pursuing knowledge or doing advocacy. If you are someone who thinks I’m naïve for believing that science education and science itself should try to function apolitically, then I can’t help you, and it is likely you are doing institutional science a disservice.

To close, I’d like to point out the obvious hypocrisy that neutral observers are bound to identify among academics of the type that argue “teaching Mendel makes racists.” They will see that the evidentiary standards are different for pet theories than disfavored ones. It isn’t hard to find an abundance of cases of this. Often, the same individuals who are eager to argue that Mendelian genetics provides succor to genetic essentialism and race realism and campaign for a sudden, radical revision to an age-old curriculum also like to set forbiddingly high evidentiary standards when judging modest sociobiological claims, specifically the claim that many social and psychological traits are under meaningful genetic influence. Selective demands for rigor giveaway the game. The primary motivations and ultimate ends are political. In some very extreme sense, any pedagogical program is political, but the inculcation of Western liberal ethics has never and will never require intervention in basic genetic concepts.

Leave Mendel be. He did something great.

Related Conversation on Substack Notes

This is obviously a debatable point given that we really have no idea how contingent or determined the course of these specific events were.

This is a long-running concern for many with left-liberal or progressive political beliefs or other ideologies premised on libertarian free will.

I’m sorry if this sound like mumbo-jumbo so far. I really wish race wasn’t dragged into what otherwise would be a somewhat low stakes pedagogical debate, but apparently cheap rhetorical tactics that serve larger and likely unachievable political goals supersede more mundane considerations about what’s a rationale and reasonable way to approach teaching novices about a complicated and nuanced subject of which a proper understanding is predicated on mastering the basics in other subjects like probability and statistics. Then again, if ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

The reasons for this association isn’t merely historical accident. Most human traits of social interest, things like height and intelligence, are influenced by an enormous number of genes (as well as other factors). The first eugenicists already had a sense for this.

Apologies, this is an indirect reference to "The Death of the Author," an essay published in 1967 by Roland Barthes. The general idea here is that there is inevitably meaningful distance between the originator of an idea and that idea itself. When it comes to the abstraction of science, this should be immediately clear. One can be taught the basic of gravity or quantum mechanics without having to be taught anything about Isaac Newton or Max Planck. It shouldn’t require saying, but, obviously, individuals of any variety of moral character can make intellectual contributions. Their accomplishments or abstractions are not somehow innately tainted simply because they may have been morally dubious person. To be so under the power of this guilt-by-association logic is utterly irrational and is not conducive to a healthy intellectual culture.

This paradigm is evolving as polygenic risk scores being to enter clinical use. Additionally, the use of polymorphisms to inform medical care, pharmacogenomics for example, has also been explored and is offered. However, there are few unambiguous successes to point to at this time.

It should be incumbent on any would be reformer to first do the due diligence of surmounting Chesterton’s fence.

This is why many have concluded that the most ethical approach to inequality is to grow the available pie as fast as possible. The more non-zero sum interactions available to individuals, the more likely a broad and stable level of prosperity and happiness can be achieved.

I understand this is a bit of silly and perhaps inappropriate comparison, but it has to be made when the latter work seeks to erase the history made by the former. It is really the anti-Mendel advocate who force us to make this comparison.

Much more important than the controversy over whether "math is racist." However, I think if we step away from the topic of race, and focus on eugenics more broadly, then the topic of Mendelianism does gain more relevance. Not something to be hysterical about, but good to "teach the controversy."

I was amazed to read, via Sasha Gusev, that most genes are much more polygenic than I had imagined. For traits like alcoholism, or impulsivity, or introversion, there are so many contributing genes that eliminating those behaviors via "eugenics" becomes much more difficult than "sterilizing all the blondes to eliminate blondness."

Given my high school level of genetics knowledge, I didn't understand this, and I thought you could just "sterilize the alcoholics, to get rid of the alcoholism gene." It's more complicated than that -- polygenic traits are much more resistant to selective pressures than monogenic traits, even under strict or harsh conditions. Adding nuance and understanding is always good.

You could also use the atomic model as an example where an inaccurate heuristic is still used in the classroom. We still learn in high school that the protons, neutrons, and electrons are little bowling balls in a little solar system.

This is a really good way to put it: “Genetic concepts like epistasis, linkage, penetrance, and expressivity are often easier to grasp when a foundation of Mendelian genetics has been established”.

It’s the same way we teach the atomic model. We don’t jump straight to electron clouds.