A Mysterious and Deadly Inheritance

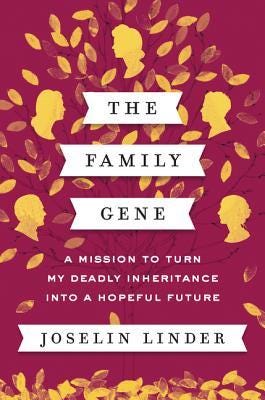

Joselin Linder's moving medical memoir, The Family Gene, reminds us that research findings should be shared faster and that many important yet simple questions in human genetics remain unanswered.

In our high-tech genomics age, it can be easy to come under the impression that all Mendelian traits (i.e. those associated with the highly penetrant effects of variation in a single gene) have been accounted for by prior research efforts in human genetics. This is understandable hubris, and it is incidentally yet eloquently dismantled by The Family Gene, a moving medical memoir by Joselin Linder. The memoir also highlights the unfortunate reality that many scientific findings remain unpublished and unavailable to the broader public.

It Can’t All Be The Liver, Can It?

The Linder family’s harrowing experience with their mysterious and gruesome condition narratively begins around the 1990s with Joselin’s father, Bill, who was a respected local family physician in Columbus, Ohio. In middle age, Bill began presenting with a slew of symptoms that perplexed doctors and worsened over time despite dogged and expert medical care. With the exception of an experimental open heart surgery to correct congenital pulmonary valve stenosis (noticed as a heart murmur) in early childhood, Bill otherwise had an unblemished history of good health. This made his condition all the more confusing and upsetting to his family.

Bill’s zeal for life and medical knowledge prompted an aggressive diagnostic odyssey. His condition was notably characterized by swelling in his legs (lymphedema), but the usual causes of this were ruled out. There was no cancer, no congestive heart failure, no liver failure, no renal insufficiency, etc. Nevertheless, the swelling progressed. As nasty complications arose, it became necessary to drain the fluid causing the swelling. It was identified as chyle, a bodily liquid described as “yellowish,” “milky,” and “fatty.” Meanwhile, it was also noticed that Bill’s serum albumin levels were perilously low. He was simultaneously starving and swelling. This discovery landed Bill on a drab very low-fat diet that almost sapped his enthusiasm for life.

In the mid-1990s, Bill and the Linder clan traveled to Boston Children’s Hospital for special medical consultations and evaluations. Bill, at the time, was also fighting off a serious infection. While commiserating with extended family, Joselin’s great-aunt Joanie, wife of Bill’s uncle Nathan, connected Bill’s symptoms with those of her late husband and his premature death. This realization is momentous. It raised the possibility of a genetic cause behind the mysterious condition. Additionally, this realization caught the interest of a brilliant cardiovascular geneticist named Christine “Kricket” Seidman, who trained under a foundational figure in the field of medical genetics, Dr. Victor McKusick. Despite the attention of luminaries, Bill would still expire a couple years after the trip to Boston at the age of 49. The pace of biomedical research is tortuously plodding relative to the pressing mortal stakes of serious illness.

Nathan and Bill are not the only victims of this deadly and mysterious genetic condition. Shortly after Bill’s death in 1996, it was noticed that Bill’s brother Norman was similarly afflicted as was Bill’s mother Shirley, though her presentation was significantly milder. As Seidman’s team of scientists worked through the case, additional members of the family were identified as likely carriers of the mutation, including Joselin herself and her sister Hilary.1 Still quite young at this time, Joselin and her sister firmly resolved to halt this deadly condition in its tracks, promising each other not to pass it on to their prospective children. To do this, the genetic cause would need to be identified.

Then, in 2002, a significant breakthrough was made. A post-doctoral research fellow in the Seidman lab named Meredith Moore successfully mapped the candidate gene to the X chromosome.2 The finding offered a path forward for presenting future transmission of the disease and a plausible explanation for the milder presentation of the female carriers. They harbor two copies of the culprit gene, one that is mutated and one that is fully functional, while the male carriers just have the one mutated copy. The female carriers are still affected because of the process of X-inactivation, where one of the two X chromosomes in every cell of the body is randomly chosen by cellular processes to be packed away into what’s called a Barr body. This preclude almost all gene expression from that inactivated chromosome. This leaves roughly half of the cells of a female carrier affected in the same way as the cells of a male carrier, and, apparently, the functional copy the female carriers do have simply isn’t enough to entirely stave off the condition over a human lifespan.3

After the finding of X-linked inheritance, the trail runs cold for a bit. Joselin, her sister, and other relatives like her first cousin once removed (Valerie) experience a number of health incidents and/or undergo various procedures. This is an especially fragile and uncertain time for Joselin. Then in 2014, Joselin gets the final piece of the puzzle. Dr. Kricket calls her in for a presentation. The culprit has been identified and a plausible disease mechanism worked out. Joselin and her family have an extremely rare genetic variant on their X chromosome. It is so rare that it is thought to be unique to their family. It is thought to be a recent founder event that first appeared in Joselin’s great-great-grandmother Ester Bloom, who also showed symptoms of the condition.4 The variant (aka mutation) affects a gene that Dr. Kricket alleges controls the pressure of the vasculature in the liver. The carriers are born with narrowed veins in the liver (and some other places too like the heart, though they don’t seem to cause issues there) and this requires compensatory vasculature to spring up, but eventually this juncture of the circulatory system fails and fluid starts to leak and build up in places it shouldn’t. This accounts for the collection of weird symptoms experienced by family members: lymphedema, gastric varices, splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, etc. Dr. Kricket’s ultimate diagnosis is that Joselin and her affected relatives have an X-linked dominant vasculopathy that doesn’t onset until adulthood and primarily causes disease by disrupting portal circulation.

With this knowledge, Joselin is better able to set aside her worries about her fragile grasp on life and make peace with her choice to forgo motherhood. It also gives her sister the confidence to become a mother to twins using IVF with pre-implantation genetics. The power of genetic science delivers a modest happy ending for the afflicted family, resolving five generations of medical mysteries and providing closure on the tragic losses sustained.

A Medical Memoir - Not a Scientific Publication

Unfortunately, it doesn't appear that any of the tantalizing genetic findings described in Linder’s memoir have made it into any scientific publications. I’ve done quite a bit of searching and come up empty. This is a bit perplexing since Linder’s book was published in 2017, shortly after the discoveries of the Seidman lab.5 There are any number of reasons why these findings may have been held in reserve or have yet to appear in print, including uncertainty about whether the findings are legitimate, uncertainty about the disease mechanism, inability to publish the work in a desirable prestige journal, more pressing research priorities, privacy concerns from the family, etc. The manuscript may even be held up in review right at this very moment. Who knows!? It’s a frustrating state of affairs.

It is a sorry commentary on the mechanisms we use to disseminate scientific research where the prerogatives of individual investigators and private institutions take precedence over the furtherance of public knowledge, which is the basis on which the research is justified and funded in the first place. At least twice in the course of two-and-a-half decades, the Seidman lab have expertly unearthed findings buried in the unique Linder/Bloom genomes and yet opted not to share these findings with the broader scientific community. Findings languishing in file drawers hold back scientific progress, especially in genetics, where it is absolutely crucial to gather as much data as possible on the functional effects of variants. Rare biology can teach us so much!

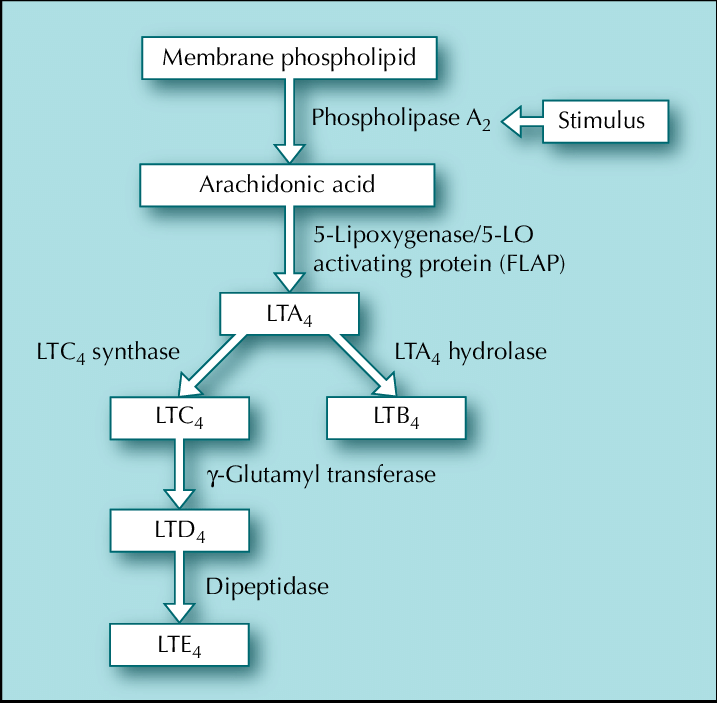

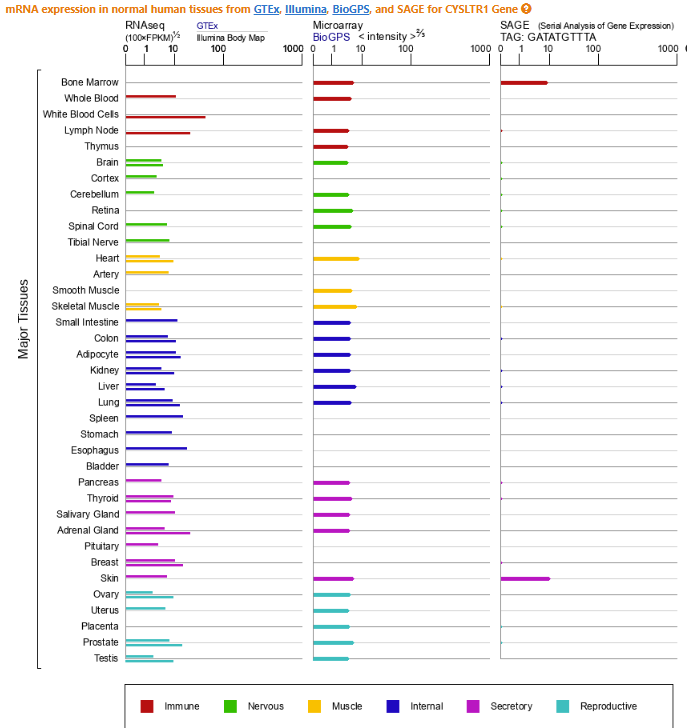

Despite our lack of hard data and Linder’s omission of much of the molecular specifics concerning the gene, the variant, and the disease mechanism. I will speculate here about what this unique founder mutation may actually be. Per Linder’s disclosures in chapter 32 of her book, we know the gene is involved with cysteinyl leukotriene biology and is on the X chromosome. This strongly implicates CYSLTR1, a gene that encodes one of two cysteinyl leukotriene receptors in the genome. CYSLTR1 is a member of the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family, the largest receptor family in the genome. GPCRs are characterized by their seven transmembrane alpha-helical domains and, in the case of CYSLTR1, have an extracellular domain that binds cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs) like LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4, which are inflammatory lipid mediators. When these CysLTs interact with extracellular façade of CYSLTR1, the rest of the receptor conducts this signal to the interior of the cell, which then triggers a cascade of intracellular activity that leads to smooth muscle contraction. Typically, at least in the well-described bronchial pathophysiology of asthma that CysLTs have been implicated in, CysLT activation of CYSLTR1 drives vasoconstriction.

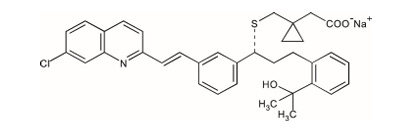

Despite the high likelihood of CYSLTR1 being the gene of interest in the Linder family, the variant of interest is much more ambiguous. This is not only because it isn’t clearly described in the book, but the putative effects of the variant aren’t made eminently clear either. This isn’t the author’s fault as these are simply details that would be expected in a scientific manuscript not in a memoir. The possibilities for the variant range between some type of gain-of-function variant to some kind of non-coding regulatory variant. Fortunately, I think we can rule out loss-of-function variants based on the information from Joselin. First, she mentions that her family is being treated with an asthma drug called Singulair (montelukast), which is a CYSLTR1 antagonist.6 Second, she reveals that Dr. Kricket believes that both the interaction between the CysLTs and CYSLTR1 and the overall levels of cysteinyl leukotrienes in her portal circulation over time are involved in the disease pathophysiology. The latter point is specifically referenced with respect to the delayed onset, suggesting sophisticated feedback loops responding to years of a basal level of errant signaling are required to drive disease.

The reasons I don’t just simply opt for the gain-of-function effect explanation, which seems most likely, is that CYSLTR1 has a somewhat atypical gene structure and the disease presentation is largely localized to the liver despite the otherwise global expression of CYSLTR1. The apparent liver-specificity suggests a possibility that tissue-specific gene regulation may have a role in the Linder family condition.7

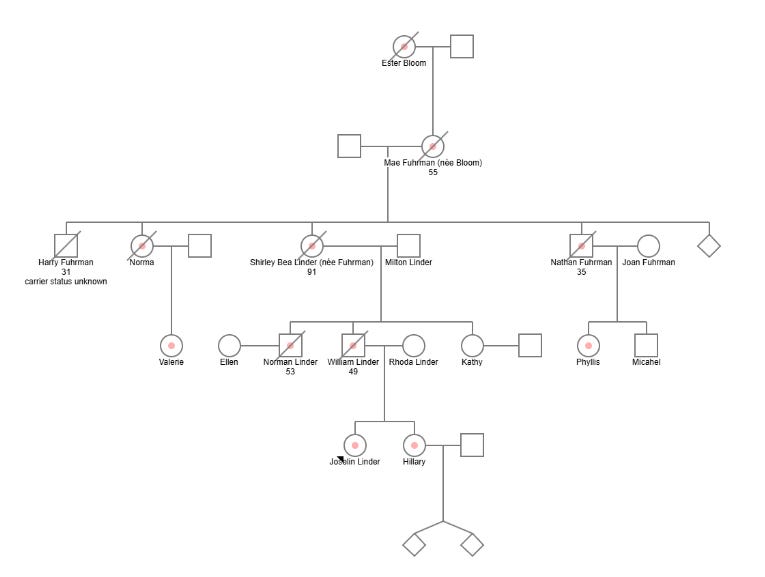

Due in equal parts to my interest in the case and frustration with the lack of published scientific data. I did my best to re-construct a simple pedigree for the family.8 It, of course, starts with the alleged founder Joselin’s great-great-grandmother, proceeds through four generations of the family and then ends with Joselin and her sister. Unfortunately, I was unable to confidently map all of the described verified 14 carriers of the private variant and their familial relationships. Joselin mentions that five of her cousins are affected carriers but only names two of them over the course of the book, Valerie and Phyllis. Joselin also isn’t clear about whether there are any carriers still of reproductive age, though the implication of the book is that there are not, meaning there will be no future affected carriers.

Undeniably, there is something wonderfully positive about putting an end to this dreadful example of human suffering, but it also prompts an uncomfortable question for those hoping to make future progress in rare disease genetics. If we can so easily deploy family planning interventions based on knowledge or even just suspicions, will we have much opportunity to make future genetic discoveries using family models? There are alternative routes to discovery available to genetics beyond family studies, but the rarity of these events, the development of reproductive technology, and, to a lesser extent, declining fertility do appear to lower the ceiling on the probability of happening upon families like the Linders. This despite the fact that the Linder example itself illustrates that much lurks in the genome to be discovered.

We should prevent disease where possible, but we should also work harder to find familial genetic diseases where they exist and report them out to the world. When the afflicted lineages have withered as they’re doomed to do anyway, we can then direct discovery efforts elsewhere. My point is we’re leaving some much low-hanging fruit unplucked that it is over-ripening and it will shortly be gone due to the technology already available to us. This may forever keep some knowledge about the genome beyond our grasp.

To play us out, listen to Joselin Linder’s story in her own words”

Prior to mapping the variant linked to the condition, the putative, yet-to-be symptomatic carriers were identified by the heart murmur caused the narrowing in their pulmonic valves.

Based on Joselin’s description, Moore conducted a classical linkage study on the Linder/Furhman/Bloom clan drawing on at least 5 known carriers and some undisclosed number of healthy non-carriers in the family. This narrowed things down to a region of the X chromosome with roughly 30 candidate genes. Eventually, Moore was able to update this work with more familial carriers and non-carriers in order to narrow down the locus further, which Joselin describes as being associated with asthma risk. There are two loci on the X which are notably associated with asthma, CYSLTR1 and IL1RAPL, but for reasons that will later become clear, I think Moore identified a variant close or within CYSLTR1.

This type of inheritance pattern is called X-linked dominance. The Linder family’s unique condition also shows a delayed onset, meaning it doesn’t cause disease until at least adulthood and sometimes well into middle age.

Joselin never discloses how Ester Bloom was identified as the founder other than there being some evidence she was affected. However, it is likely the Seidman lab conducted some haplotype analysis and were able to provide a proximal date for the mutation. My evidence for this is that Joselin does take time in her memoir to describe some other known founder variants and includes the estimate date of origin.

During media tours associated with the book or other appearances by Linder, she’s commented that the Seidman lab has been working on developing mouse models of the family’s variant. Her comments suggests the Seidman lab has run into some trouble with these efforts.

They’re also treated with antihypertensive drugs.

Here’s the skinny on CYSLTR1 gene structure: A typical gene will have seven to nine exons where the first and last exons are partially coding or even entirely or mostly non-coding (especially at the end of the gene). CYSLTR1 has a single coding exon, which isn’t actually unusual for a GPCR gene, but it has four other non-coding exons that precede it, of which exons 2 through 4 are subject to alternative splicing, which is more unusual. This structure suggests some complex gene regulatory mechanisms govern CYSLTR1 biology. This is also underscored by a large number of possible transcriptional start sites in the constitutive first non-coding exon. Given that CYSLTR1 is expressed throughout the body but the Linder family’s symptoms are most concentrated in the liver, I wonder if this suggest the variant falls in the non-coding portion of the gene. Alternatively, it also seems possible the variant of interest increases the affinity of CYSLTR1 for CysLT inducing vasoconstriction and thus the montelukast competitively disrupts this interaction. There may be feedback mechanisms that seek to lower CysLT over time which contribute further to dysfunction in portal circulation. This last bit may account for Linder confusing commentary.

Per Linder’s descriptions in the text, here are the fourteen known affected family members:

Joselin Linder [Proband]

Joselin's Sister Hilary Griffith

Joeslin's Great Grandmother Mae Fuhrmann [Patient A in Moore’s linkage study; died at 55 years old]

Joeslin's Grandmother Shirley Linder [a mildly affected carrier - died at 91 years old]

Joselin's Great Uncle Nathan [Patient B in Moore’s linkage study; died at 34]

Joselin's Father Billy Linder [Patient C in Moore’s linkage study; died at 49 in 1996]

Joselin's Great Aunt Norma [Patient D in Moore’s linkage study]

Joselin's Uncle Norman Linder [Patient E in Moore’s linkage study; died at 53]

Joselin's Great Grandmother Mae [affected] died at 56

Joselin's First cousin once removed Valerie (Norma's daughter)

Joselin's First cousin once removed Phyllis (Nathan's daughter)

At least three other unnamed cousins of Joselin.

Thank you for all the work and information you put in to this article. I just listened to this case on a podcast, and as someone in the medical field who loves mysteries and genetics, it really bugged me that I couldn’t find any info about this disease.

Fascinating, Stetson!