A Brief Genetic History of Europe

A tour of highlights from A Short History of Humanity: A New History of Old Europe by Johannes Krause and Thomas Trappe.

tl;dr section:

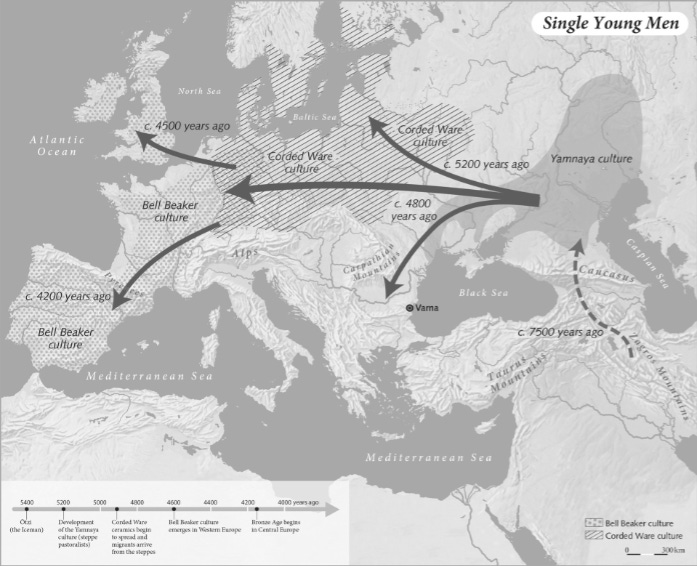

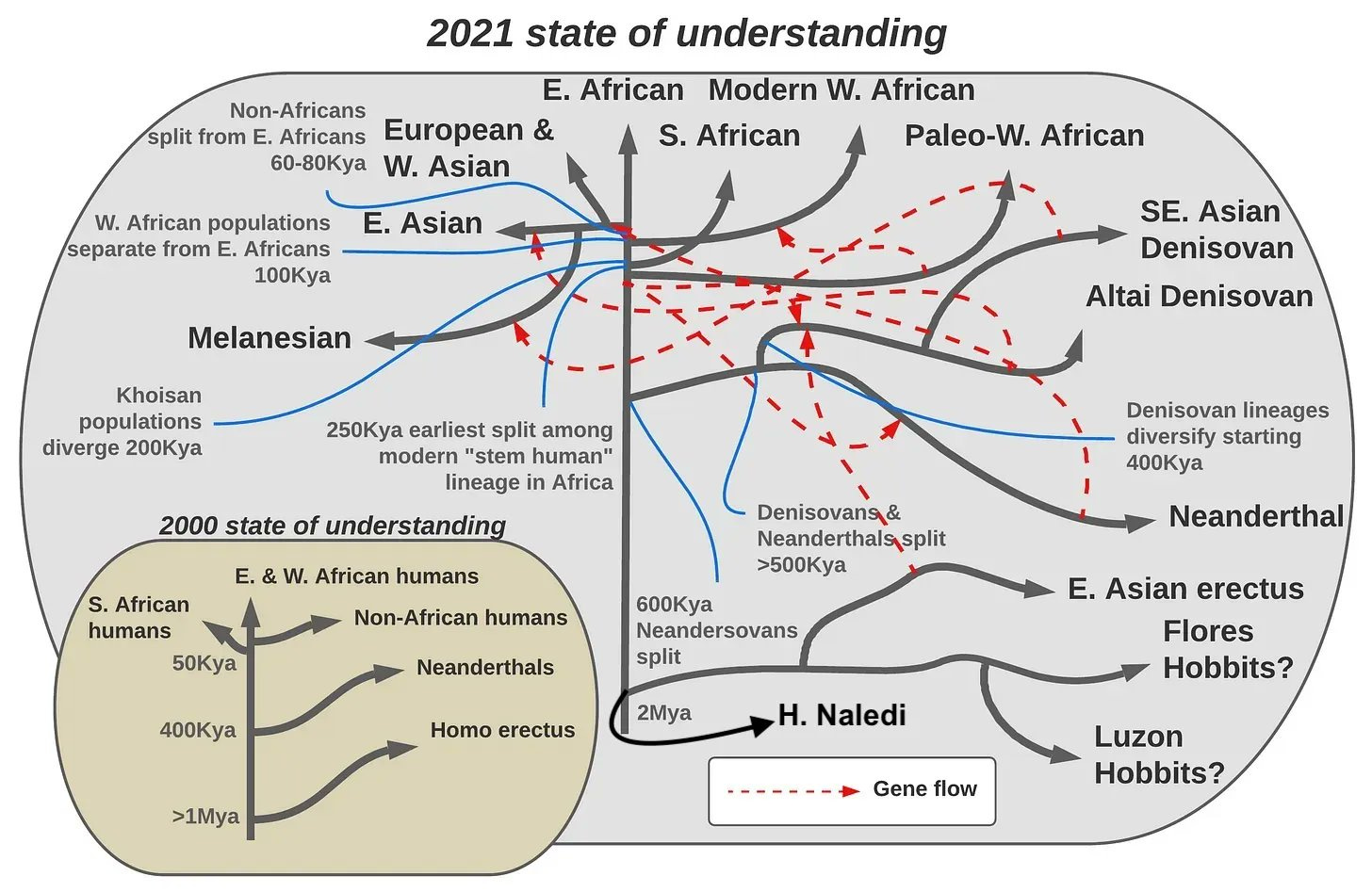

A Short History of Humanity: A New History of Old Europe presents a “four-component”1 population history for modern Europe enabled by advances in the study of ancient DNA (aDNA). The complex story stretches back more than 40,000 years, and it is a narrative marked by incessant migration. There are other important biological, technological, and cultural dynamics at the margins too. Successive waves migrants have created the four part mixture of ancient hunter-gatherers of Europe and Asia and the western and eastern populations of the Fertile Crescent in the Neolithic Era and Bronze Age, respectively. The Fertile Crescent populations contribute the overwhelming majority to the genes of modern Europeans. The last major genetic changes occurred 8,000 and 5,000 years ago and explain the fundamental to this day.

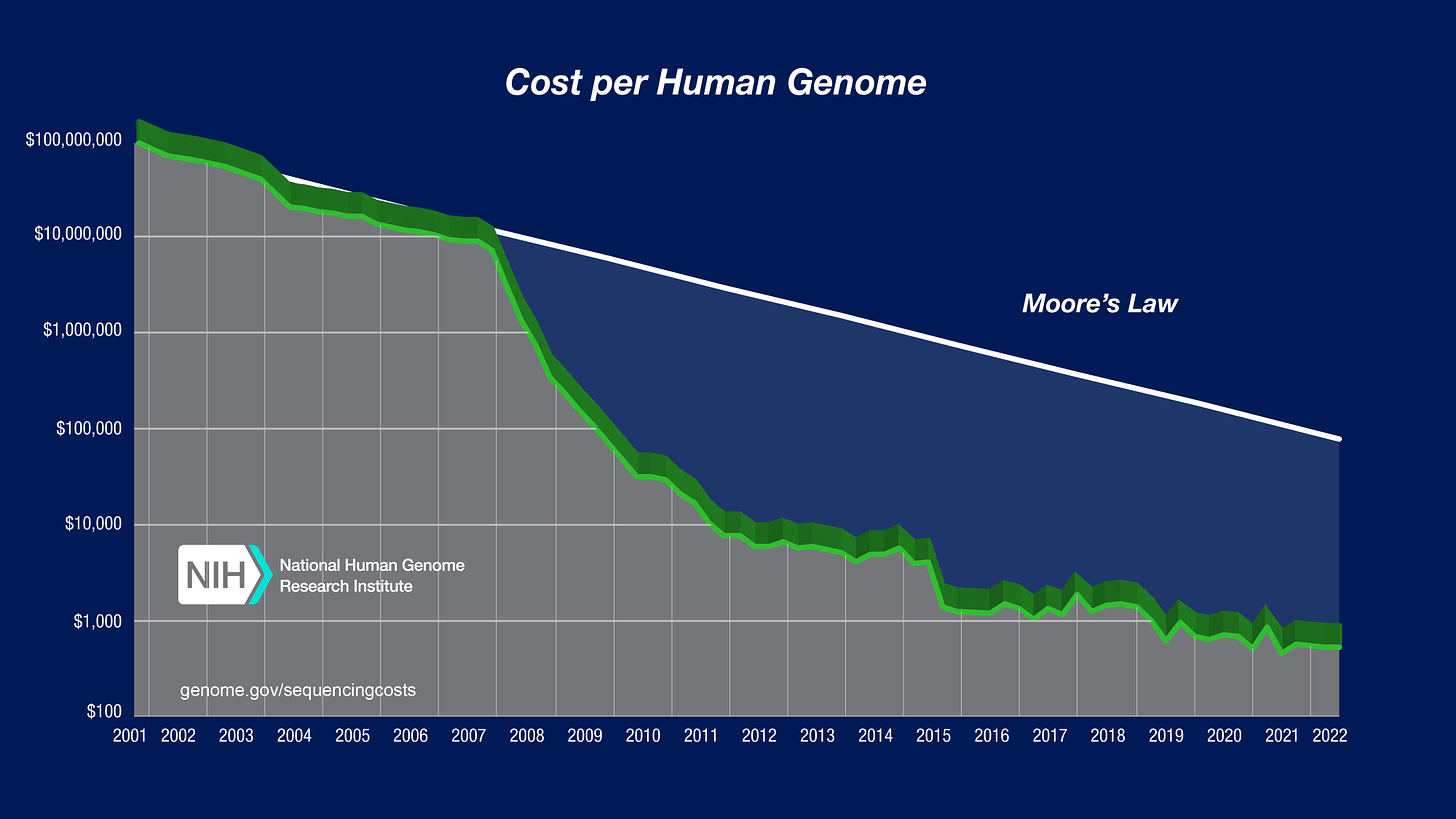

It is hard to get a good sense for how broadly and deeply the technical advancements in genomics are appreciated. Given my uncertainty about this, allow me to give readers a sense of the innovation that’s been achieved. Roughly a quarter-century ago, it cost nearly $3 billion and years of time to sequence one human genome. Today, many genomes can be sequenced for $200 a piece in a matter of hours. The staggering pace of this progress is typically communicated with a chart showing the genomics cost curve (see below).

The genomics cost curve is only a peek at the total innovation that’s happening in genomic sequencing. Yes, the next-generation sequencing (NGS) era has facilitated dramatic increases in throughput and cost savings, but there has also been amazing breakthroughs in related methods and applications. One of these advancements includes the ability to accurately obtain and sequence ancient DNA (aDNA) and effectively analyze the resulting data for historical insights. The Nobel laureate geneticist Svante Pääbo and the Harvard geneticist David Reich have contributed prodigiously to these efforts.

Correspondingly, there has been an outpouring of content attempting to communicate these findings to other scholars, eclectic hobbyists, and the lay public. I can slot parts of myself into all three of the above categories. Subsequently, I have picked up several titles on aDNA findings and related topics. I’m also a regular reader of Razib Khan’s Unsupervised Learning Substack, which I strongly recommend.

The latest book I’ve finished, A Short History of Humanity: A New History of Old Europe by Johannes Krause and Thomas Trappe, provides a comprehensive yet brief history of the peopling and re-peopling of Europe. Their work is based on what aDNA has taught them in conjunction with other archaeological and linguistic evidence. There are essentially two central claims presented. First, there have been three(ish) major waves of major migration in deep time that are responsible for the genetic composition of Europeans today.2 Second, since the conclusion of the final wave, roughly 3000 years ago, the genetic history of Europe has been largely unchanged. This final wave of migration from the Pontic Steppe (the Yamnaya culture) contributed dramatically to the genetics of modern Europeans, replacing a substantial portion of the prior residents, i.e. the Neolithic farmers who emerged from Anatolia. Since then, the biggest population-level upheavals have come from pathogens like Bubonic plague. Of course, today there’s a great deal of sociopolitical concerns about immigration to Europe from regions in Asia and Africa. The authors see the migrations patterns of today as an an innate feature of humanity given its prominence in the past.3

As an aside, some readers may be a bit confused by the above language. It appears to collapse the observable diversity of contemporary Europeans, identifying them as a single group. I think a good way to think about these things is a reticular metaphor, where Krause and Trappe’s focus is on the source of the main branch of European ancestry rather than all the smaller peripheral branches. It is true that genetic technology is sensitive enough to trace particular genetic characteristics to particular regions and that this can overlap quite nicely with received understandings of national or cultural identities. This is not the author’s focus because they are curious about European origins not the more superficial differentiation of our recent era.4 But before jumping back to the question of origins, let’s satisfy the curiosity that direct-to-consumer ancestry testing kits from companies like 23andMe have sparked. Why can we trace these fine differences? Well, the basic principle behind this is helpfully summarized at the beginning of the book:

The closer the geographical proximity between two people, the more closely they are likely related, because less time has passed between their most recent common ancestor. The genetic distance between the British and the Greeks is thus the same as between the Spanish and people from the Baltics, while Central Europeans sit somewhere in between. If you plot the genetic distance between Europeans on x- and y-axes, the resulting coordinates are nearly identical to a geographical map of Europe.

Our Human Cousins

Although it is likely many readers were made aware of the human diversity in our deep past by trips to natural history museums or television documentaries on archaeology, I think Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens played a special role in catapulting awareness of our close cousins into popular consciousness. Neanderthals have accrued the most attention on this front of course - also a popularity that stretches back well before Sapiens and the explosion of aDNA research.

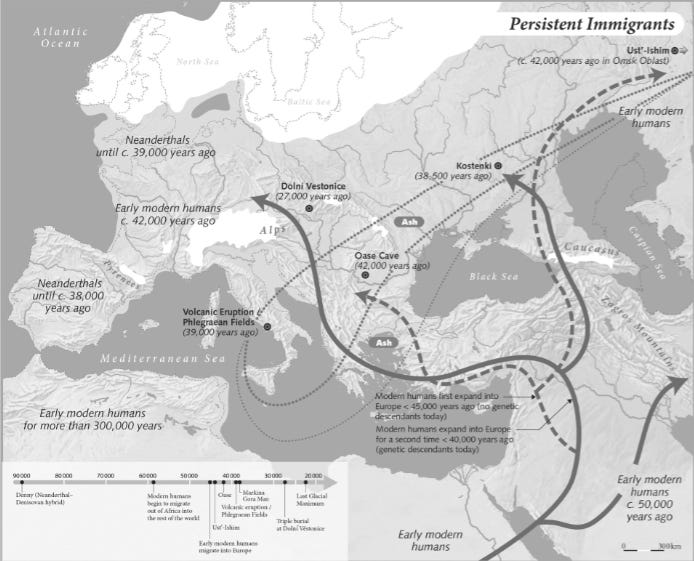

There are many mysteries that still remain about Neanderthals. Did they have the capacity for complex language? What led to their disappearance circa 39,000 year ago? However, we do know they lived in a belt stretching from the Iberian Peninsula to the Altai Mountains and were mainly clustered in what is today’s southern France and also in the Near East. Their residence in these regions corresponded to an Ice Age and thus they were largely isolated from other human populations by glaciers and inhospitable conditions.

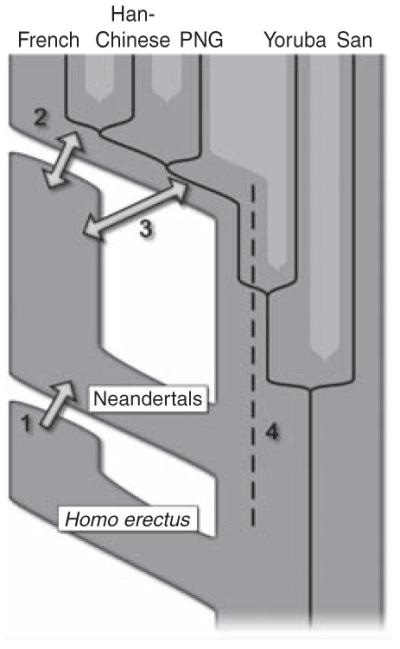

Recent study of aDNA has taught us a lot about different types of archaic humans, including how our relatedness and the continued persistence of their genes in us. For our Neanderthal brethren, this revelation came courtesy of ~400,000-year-old set of remains discovered in Spain. Krause, a member of Pääbo research group and in collaboration with Reich, published a draft of the Neanderthal genome in 2010 and used the available aDNA from Neanderthals to demonstrated that thet comprises 2-2.5% of the genomes of today’s Europeans, Asians, and Australians.5 Additionally, Krause and his colleagues were able to speculate about when and how Neanderthal mixture was contributed to modern humans (see figure below from the 2010 study).

It is worth dwelling on our ancient cousins a bit before jumping into the genetic history of Europe because these cousins played an early role in this process. We can still see their genetic contribution today. Their story also emphasize the complexity of human evolution. Humans did emerge out of Africa, but there were still significant evolutionary changes happening to humans outside of Africa. It is awe-inspiring how aDNA provides a glimpse into this dim and distant past.

The First Sapiens in Europe

Krause and Trappe assert that the best evidence indicates that modern humans moved north out of African at least 200,000 years ago. However, these migration attempts appear to have been abortive. It wasn’t until ~40,000 years ago that two big migrant pushes allowed for a more established presence. These early Europeans are often referred to as the Aurignacian and other related groups are called Gravettians and Magdalenians.6 The Aurignacians were of course hunter-gatherers who were quite vulnerable to the rapid and severe oscillations in the climate of the Upper Paleolithic period. The Last Glacial Maximum appears to have trapped a contingent of Aurignacians on the Iberian Peninsula who persisted for roughly 14,000 years there until the end of that Ice Age.

After the ice receded, it appears Aurignacian hunter-gatherers traveled back to central Europe and mixed with another somewhat mysterious group. The mystery group arrived from the Balkans around 18,000 years ago. They’re the same group that contributed significantly to modern-day Turks, Kurds, and North Africans but otherwise little is known about them.7 Over the next 3000 years, the hunter-gatherer populations from Iberia and the Balkans mixed in central Europe becoming a homogenous population. They were “technologically highly developed hunter-gatherers with blue eyes and dark skin.”

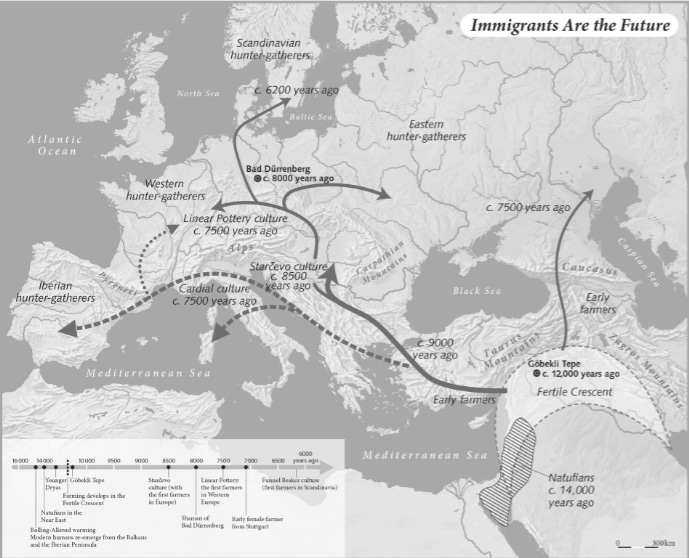

The Farmers Move In

The next peopling of Europe is linked closely to the shift to agriculture. The origins of this story are of course in the Fertile Crescent. Before aDNA evidence was available there were two equally plausible theories of how agricultural was brought to Europe: 1) farming technology was appropriated by the people of Central Europe from their Anatolian neighbors or 2) the Anatolians of the Fertile Crescent expanded westward and brought farming along with them. This latter theory has been shown to be the case. Specifically, there was a 2014 findings of a Swabian woman’s remains which showed Anatolian genetics that were quite differentiated from the prior hunter-gatherer population. The Neolithic farmers from Anatolia settled all across Europe. The in-place hunter-gatherer population there didn’t entirely disappear when the farmers arrived. However, they were subject to some crowding out and became less prevalent. There is actually some evidence to suggest they coincided fairly peaceably under the right circumstances.

It was also during this time that stronger selection for lighter skin pigmentation began. This was partially a function of the change in diet. These Anatolian farmers ate less meat and fish than hunter-gatherers and thus had a greater need to synthesize vitamin D. There was some beneficial pleiotropy as well given that the relevant mutation that decreases melanin production also increases cold and pain tolerance. Unfortunately for the Neolithic farmers their dominance of Europe was short-lived. Only a few thousand years later and a new massive wave was on its way.

Stepping into Modern Europe’s Genetics

In the Bronze Age, a mass of herders on horseback from the eastern portion of the Eurasian steppe swarmed Europe. This population was actually comprised of two components, one from the Pontic steppe descended from North Eurasians and one from present-day Iran. This group is often referred to as the Yamnaya culture. They used bronze to make weapons and built large burial mounds called barrows. They were also significantly taller than Europe’s existing residents. Although it isn’t entirely clear how they became so prominent, their genes came to dominate Europe. The competing hypotheses for this process include disease and/or violence. Today, the people with the smallest contribution from the steppe are Spainards, Sardinians, Greeks, and Albanians.

One of the striking features of the Yamnaya migration was that it was heavily male. This can be detected by following the genetic shifts occurring in Europe at the time along the maternal (mitochondrial DNA) and paternal (Y chromosome) lineages. 80-90% of the new Y chromosomes entering Europe were of steppe origin.8

Human Vectors Spreading Malady

After Krause and Trappe deliver the population history of Europe. They embark on an exploration of the pathogens that began to emerge in Europe as agriculture, especially pastoralism, took hold on the continent. They discuss the various plagues, the evolutionary origins and transitions of the plague, the diseases of the Columbian exchange (including whether Syphilis did indeed come from the Americas), leprosy, and tuberculosis. This section was really neat in that it showed how we can use genetic approaches on biological specimens other than ancient humans to still learn a great deal of human history.

The Past is (likely) the Future

The takeaway for the authors is that we should expect our human future to be like our past. Here, they specifically mean migration will be a common mechanism of genetic and cultural exchange. They don’t want readers to romanticize or be resigned to this reality. Migrations will inevitably cause disruptions, and the human family tree will become even more intertwined. We have to find a happy medium that enables both conservation and stability and innovation and change.

An additional takeaway offered by the authors concerns the importance of genetics to history and vice versa. I think this is an overwhelmingly important point. I welcome a strong merger between these fields and am eager to see the interesting things such consilience can reveal about the past.

A Short History of Humanity: A New History of Old Europe offers a lot of pithy insights from ancient DNA and other fields that study human history. I think along with David Reich’s Who We Are And How We Got Here, it is one of the higher-yield popular science works on the field. I strongly recommend it to anyone interested in these topics.

Sometimes they say three instead of four. This just comes down to whether they lump or split the hunter-gatherer component. This is the smallest contribution so it likely feels silly to split sometimes. There is also the Neanderthal fraction in there which is set aside.

The three dominant genetic components on the European continent today arise from the Eastern European steppe 5000 ka, Anatolian farmers 8000 ka, and early hunter-gatherer from 20-45 ka. Again, sometimes this final minority component is further split.

The scale of migration today pales in comparison to past migrations that are the subject of the book. Nonetheless, immigration is an incredibly fraught political issue. One that in some respects dominates the domestic political discourse of many European nations. One has to imagine that these migrations in the deep past sparked a even more tumult, though the lack of robust national/cultural identities presumably created different dynamics.

The authors are of course careful to point out that even their question of European origin doesn’t speak to the erroneous but sometimes seductive concept of “true origins.” All modern humans share a common ancestral origin in Africa. Modern human populations have mixed differently at the margins with other ancient humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans, but this happened after modern humans migrated out of Africa. Denisovans themselves are actually a branch off of the Neanderthal line. This split occurred about 500 ka ago, meaning the most recent shared common ancestor with Sapiens is 600 ka.

It is believed that Neanderthals evolved from Homo erectus in Africa at least 600 ka and then migrated into Europe where they eventually mixed with Homo Sapiens, who emerged in Africa too. Thus, Europeans today are 97-98% descended from Sapiens arising in Africa and 2-2.5% from Neanderthals of who had settled in Eurasia. There are some human populations with a greater proportion of genes from our human cousins. For instance, Denisovans, an Asian branching of Neanderthals, contribute 7% to indigenous populations in Australia and Papua New Guinea.

For simplification purposes I am just going to call all early modern European HGs Aurignacians.

At least to the extent relayed by Krause and Trappe in the book.

This here refers to the R1a/b haplogroups.

Thank you for that review. On my list now.