The Child is the Father of the Man

A new memoir may startle American elites out of the "vast carelessness" of their status games. It also delivers moral messages for the wayward among us. We need whole, functional families.

Successful people tell the world they got lucky, then tell their loved ones about the importance of hard work and sacrifice. Critics of successful people tell the world those successful people got lucky, and then tell their loved ones about the importance of hard work and sacrifice.

~Rob K. Henderson in Troubled

Would you rather be rich but unloved or loved but poor? Although this coarse “would you rather” doesn't actually speak to a real-world tradeoff, modern society may be ordered to increase material abundance but impoverish our communal and familial ties. A deep reservoir of ink has been poured into many works on questions related to the decline of civic institutions and the fraying of the American social fabric. Robert Putnam, Bill Bishop, Charles Murray,1 Richard Reeves, Melissa Kearney, and many others have highlighted and analyzed these concerning trends: increased social sorting, increased economic stratification, increased single motherhood/fatherlessness, declining social participation, etc. This work has a meaningful circulation among a segment of highly educated and affluent Americans. Often these issues ignite political or academic debate but largely within this charmed sliver. However, it has yet to coalesce into a coherent agenda or movement. Part of the challenge is that the ultimate solutions may be beyond political and technical levers. Additionally, the critical, often in fact moral, messages have been sidelined. In a general way, we know what we must do, but it is unclear if we have the will and competence to do it. And perhaps the first and most important step remains: the nature of the problem and an urgency to fix it has yet to resonate with a critical mass of Americans.

Rob K. Henderson, a young man who emerged from a tumultuous childhood in the foster system into the elite class of educated Americans, thinks we should work at remedying some of the skewed priorities of modern societies. He believes we should start with at the helm, where our elite class is playing games to get ahead while misleading other less fortunate Americans.

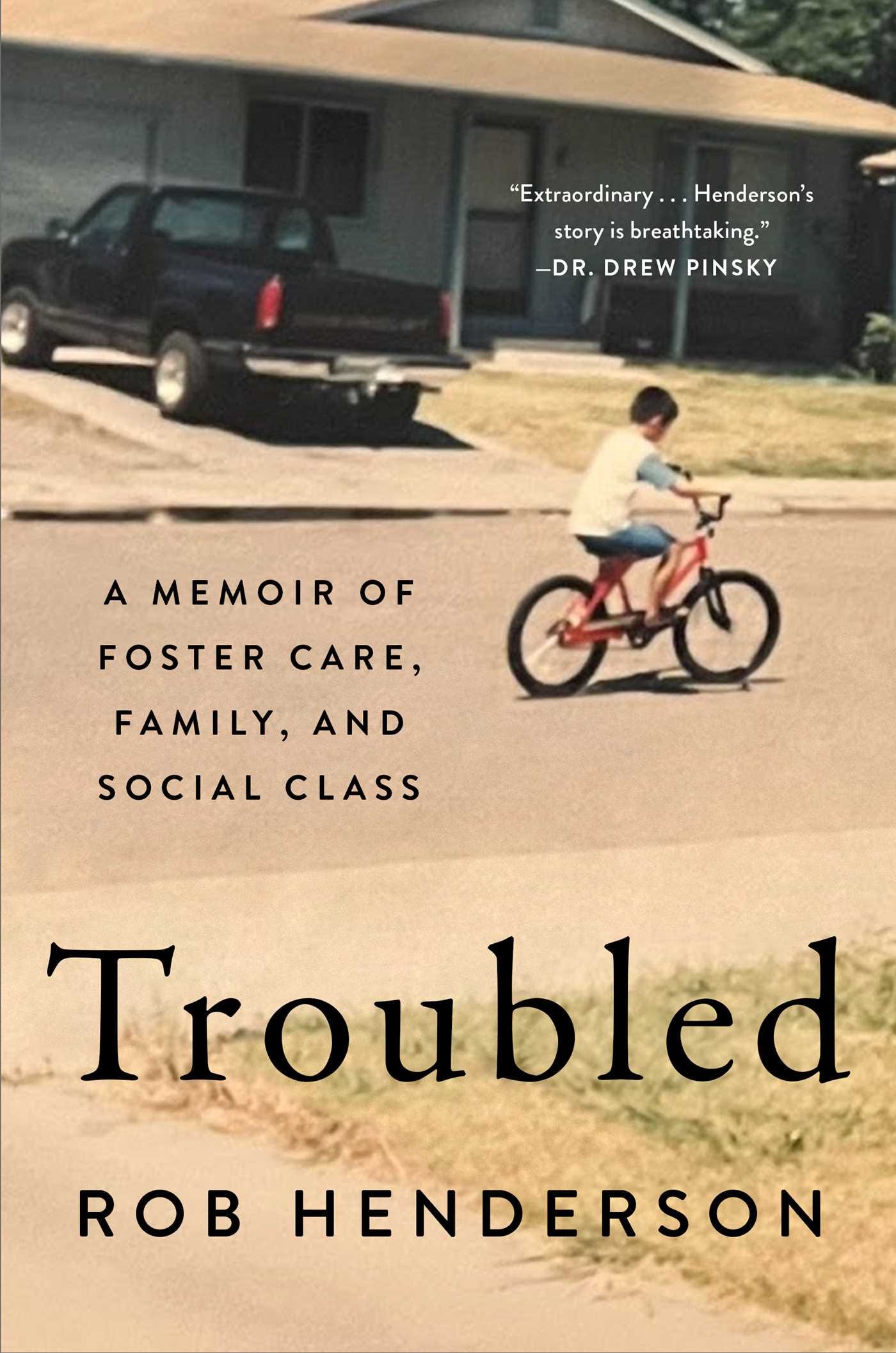

Henderson, similar to J. D. Vance2 before him, has delivered a potent personal narrative, a memoir titled Troubled. Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class has the power to reach a critical mass of Americans. It delivers in understated fashion the uncomfortable truths about the human costs incurred when social and familial obligations are shirked. It is a cutting illustration of how a solipsistic elite has intoxicated everyday Americans with “luxury beliefs” and put them behind the wheel. Luxury beliefs, Henderson’s signature idea, are beliefs that “confer status on the upper class at very little cost, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes.” Henderson identifies things like advocacy for loose sexual mores or the defunding of law enforcement as stereotypical luxury beliefs.

Henderson’s story is what Substack writer and geneticist Razib Khan referred to as “Yale or jail” in a recent podcast interview with the author. Despite some flippancy inherent to such an idiom, the variance between the two outcomes underscores the inherent precarity of Henderson’s life. He was born to a single mother, a recent immigrant from South Korea and drug addict. He has never met or known his father. Early in his childhood, California determined that his mother was unfit to parent and placed him in the foster system.

The early chapters of Troubled follow Henderson through the upheaval of the foster system. He cycles through home after home, accruing painful experiences. In a subdued tone, Henderson connects these experiences to a strong distrust of adults and a numbness that would follow him into adulthood. Sadly, Henderson’s experiences in the foster system are not unique. The pain he experiences were a byproduct of its design. It purposely keeps placements short so as to prevent permanent attachments. The system is premised on the expectation that fosters will eventually be permanently placed with kin. For Henderson, this was never a possibility.

Later, the narrative shifts as Henderson is adopted by a working-class family that settles in Red Bluff, CA. It is here that Henderson briefly has two parents, including a father figure. His adopted father is a strong disciplinarian but provides a new moment of structure and support. Again, this moment of stability is upturned. His adopted parents divorce. In spite toward his adopted mother, Henderson’s adopted father refuses to see him. Henderson’s adopted mother eventually pairs off with another woman. Henderson’s remaining childhood is spent as a latchkey kid in a rough environment. He has early exposures to alcohol, drugs, and physical danger. However, Henderson also harbors an interest in reading and demonstrates some ability to discipline his mind and body when motivated.

The precarity of Henderson’s life peaks in his final year of high school. Due to family circumstances, he lives away from the rest of his family and is taking advantage of the newfound independence, including having a car. Pick your favorite film of high school male hi-jinx, especially before our more sanitized era, and that was essentially Henderson’s experience. He is extremely fortunate none of his actions resulted in anything life destroying. After a particular rage and alcohol-fueled altercation, Henderson recognizes the unsustainability of his path. He enlists in the U.S. Air Force.

In the Air Force, Henderson benefits from structure and develops useful life skills. He also begins to learn more about American social structure by watching prestige television shows like The Sopranos. Despite this growing maturity, he’s still plagued by demons. He is able to muddle through while progressively falling into a deeper funk, a combination of depression and alcohol dependence. He breaks down and has to enter professional rehabilitation and counseling. It is in these moments that he reckons with the trauma of his childhood and is able to escape alcohol dependence and resolves to pursue success. With new direction, he strives to further his education and is able to land himself a spot at Yale.

Yale is a culture shock for Henderson. It is a dual-track education. He not only begins to learn about how the mind develops and operates in his psychology coursework, but also about the sociocultural landscape of American elites. He learns that his background is almost entirely alien among his classmates. There is a small set of those who have served in the military but few from the foster system or broken homes. He also quickly detects that his understanding of what confers status is sorely lacking as the actions and rhetoric of his classmates is often bizarre to him.

Henderson started his education at Yale during the initial crest of the Great Awokening. He was more or less a first-hand witness to the cancellation of Yale instructor Erika Christakis. Christakis’ “offense” was sending an email that questioned the wisdom of barring possibly insensitive Halloween costumes. He continued to bear witness to the hypocrisy, cold-eyed deception, and magical thinking of this class. His experiences sparked an interest in the social signaling of American elites. Eventually, he formulated the concept of “luxury beliefs,” which cleverly applies Thorstein Veblen’s ideas about conspicuous consumption to cultural beliefs and begins sharing his experiences in writing, making the pages of The New York Times.

Henderson concludes his memoir on the precipice of continuing his education at Cambridge3 and coming to the firm conclusion that he will be there for his current and future loved ones in ways that others weren’t for him. And he is happy to accept the necessary sacrifices to career and earnings in this pursuit. He also shares what has become of his friends from childhood, highlighting the outsized influence that a disruptive childhood environment can have on adult outcomes while still acknowledging the importance of making smart choices and leveraging natural gifts.

The Power of a Story

What Eil Wiesel’s Night was for the surviving the holocaust, Troubled is for coming-of-age amid the social derangement of fin de siècle America. Henderson has also recently acknowledged the insight of some reviewers that his work has a decidedly Dickensian character. This despite Henderson never being a reader of Dickens.

Troubled embodies what a great memoir of social concern should be. It captures the spirit of an epoch through the author’s eyes. It does so without sentimental indulgences or stylistic excess. Henderson is plain-spoken about his turbulent life and even somewhat reluctant with his divulgences and his moral messaging. And even when the authorial messaging is strongly delivered, Henderson manages to avoid lecturing or scolding readers. It is a beautiful demonstration of the self-discipline and restraint Henderson has developed.

I’ve lavished praise on Troubled not only because it is my authentic response to the book, but also because I think Troubled is strategically positioned to remedy some of the ills it identifies. A moving personal story can accrue influence and endure in ways that statistics and science can never dream of. This phenomenon has been the subject of study in the social sciences and is often referred to as the identifiable victim effect. It is pithily described in a likely apocryphal quote attributed to Stalin: “The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of millions is a statistic.” The tragic details of Henderson’s early life have a high likelihood of resonating with a broad audience. Only the format itself has the potential to limited its reach. So, like Henderson, I hope for adaptations and condensed versions across multimedia formats.

Not by Luxury Beliefs Alone

Henderson has a gift for detecting and distilling social phenomena. The luxury belief concept does indeed identify something that American elites practice. There are innumerable examples of elites, in sociologist Brad Wilcox’s phrasing, “talking left, walking right.” A quintessential example is of course the tech execs who promulgate addictive devices and apps but bar or restrict their children from using them. In other words, the leaders and influencers of society often advocate for permissible social rules and for freedom without accountability, while personally working hard and practicing self-discipline and modesty. This maximizes benefits in their social ecosystem while polluting the social ecosystems of others. These expressed values tend to run counter to the interests of working class Americans, including ideas about law enforcement, drug legalization, family structure, and so on. These values of permissibility can trickle down the social latter, which when acted upon often come at a greater cost to the lower rungs.

Beyond the reality of luxury beliefs though, are they really responsible for our many social ills? And even if they are a contributor, how important is that contribution? I think Henderson would and probably does readily concede that luxury beliefs are not wholly to blame. They can’t be the whole story, but they are the compelling story that he can tell. He is, in particular, irked by the missed opportunity and hypocrisy they reveal. However, there are many lines of evidence that complicate the luxury belief narrative. If elites changed their tune and started preaching what they practice, would this significantly change the fortunes of languishing and lost Americans? Would it reverse the increase of single parent homes and drive up marriage rates? I think it is unfortunately unlikely.

Now, I do think we can limited the externalities of the status games of elites by somehow attaching social rewards to more productive displays than repeating the right shibboleths and adopting radical aesthetics. But we won’t root out status games altogether, nor should we want to as we also indirectly benefit from elite competition. I think the American family is ailed by many things, including a less-than-stellar class of actual elites and deeper cultural and technological forces of disruption. Elites are not immune to these latter forces either. They have simply been able to protect themselves better from this derangement. They have ready-made material and non-material bulwarks against it, often bequeathed by their parents and synergized by their concentration in dynamic urban centers. It is the coming apart of America by class, culture, and identity that we have to reverse. We need to extend the elite bulwark. This will require actual sacrifice on the parts of elites. They will have to mix with and live among the rest of American instead of only flourishing in their bubbles and contributing only superficially to often their own pet social causes. There will have to be a real investment in building social and material capital in places that have been previously evacuated of it.

I’ve titled this review with a Wordsworth quote that Henderson references because I think it cuts to the central insight of Troubled. The early childhood environment, specifically relationships and support from typically biological parents, is absolutely critical to normal development. Henderson alleges early life instability is a greater predictor of negative social outcomes than poverty. It is a tragedy to let a child grow without love. It will only sow discord. We should act on this so that all children feel securely loved, can adjust to the wider world, and find their place in the social fabric. We will never have a perfect world nor should we foolishly seek it, but we should rededicated ourselves toward those we are obligated to.

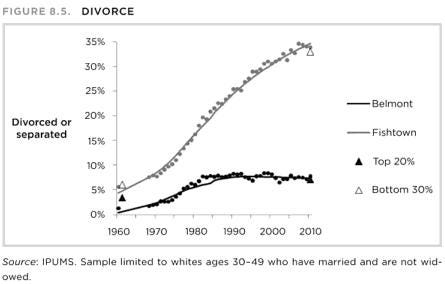

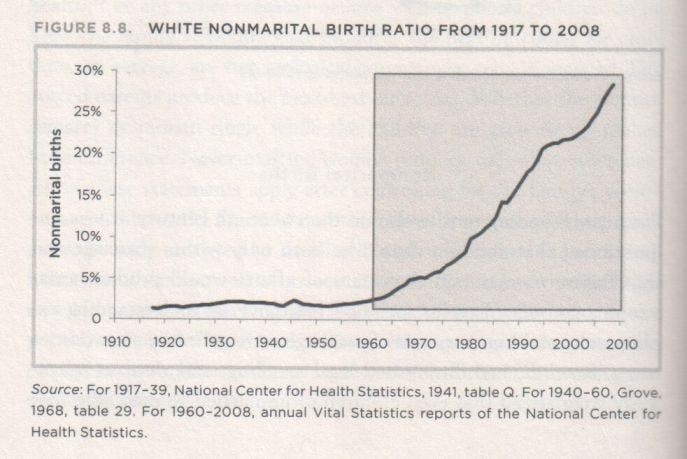

I have included two figures below from Murray’s Coming Apart, which is a closer study of the secular increase in social stratification and the rapid decline in social capital among working class Americans.

Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy was a similar memoir in terms of biographical and thematic details. Hillbilly Elegy sent shockwaves through the professional managerial class (PMC) after its publication in 2016, but its effects have faded and soured with many in that audience given Vance’s entry into partisan national politics. Henderson’s work has less of a partisan valence.

Rob has completed his PhD and now writes full-time for Substack.

There are innumerable examples of elites, in sociologist Brad Wilcox’s phrasing, “talking left, walking right.” A quintessential example is of course the tech execs who promulgate addictive devices and apps but bar or restrict their children from using them.

[Me] How is tech execs advocating for things that make them money (i.e. capitalism) “talking left”.

In other words, the leaders and influencers of society often advocate…for freedom without accountability,

[Me] This is what libertarians push for, who, in America, are on the right.

This maximizes benefits in their social ecosystem while polluting the social ecosystems of others.

[Me] Replace the first social with economic and deleting the second social and you have the driver for the environmental movement. People have always tried to get more for themselves, to become greater in the eyes of others, or as I put it, acquire prestige. It is not a left or right thing.

It seems Henderson thinks that the leniency elites give to those not measuring up in their behavior is somehow a source of their problems. Doesn’t he know that lower-class folks are more socially conservative than richer people? They know what they should do, Lord knows I’ve told them 5o times.

I’ve never met a loser who didn’t know what they *should* do. They just don’t do it (which is what makes them a loser). My wife and I are former foster parents who stayed involved in their lives and those of their offspring (who see us as grandparents). We’ve seen a lot of this.