Genes Really Do Shape Social Outcomes

Behavioral genetics may reshape society and improve the precision of educational interventions in the future.

We are at a pivotal moment in the history of genetics and genomics. It is a time when genetic engineering of the human genome has become a real possibility thanks to technologies like CRISPR/Cas9. It is also a time when we’ve begun to learn about how genetic variation in human populations shapes social, behavioral, and cognitive outcomes. Advances in both genetic engineering and social genetics may reshape society in unpredictable and dramatic ways. This Brave New World of sorts inspires a great deal of anxiety. In the minds of many, it raises the specter of eugenics, racism, and Social Darwinism.

Done in the name of social progress, these pernicious and ignorant ideologies and policies wantonly ruin the lives of many and stained the history of the early 20th century. Fortunately, there are a number of mitigating factors today that likely preclude the repeating of such nightmares. First, we now have cultural antibodies against state-based eugenics (i.e. the use of state power to control mating behavior and fertility). It is difficult to conceive how similar policies would come about given that there is no real constituency for Progressive Era eugenics in any contemporary Western state (regardless of any Twitter troll you may happen upon). This seems especially true given the extent of individualism’s influence over American attitudes about sex, marriage, and childbearing/parenthood. Second, we now have a much better understanding of genetics. And so we know just how foolish past eugenical efforts were. It wouldn’t be robustly adaptive to try and optimize the human population along a few traits like intelligence or eusociality. Attempts would simply fail or reduce genetic diversity, making us more susceptible to environmental insults as a species. Nonetheless, scientists and intellectuals would be wise to proceed cautiously with research and communicate complex ideas carefully so as not to set back the progress of genetic research. Guidelines for the way forward were recently published by the Hastings Center.

Given all this, I am particularly excited about the findings from the growing fields of sociogenomics (SG), behavioral genetics (BG), and/or psychiatric genetics. These intertwined disciplines use modern genomic techniques like genome-wide association studies (GWASs) to identify the genetic and non-genetic bases of cognition, social behavior, and its evolution. Behavioral genetics emerged from the work of statisticians like Sir Francis Galton, Sir Ronald Fisher, and Karl Pearson and heavily relied on twin-study designs for much of its history. Now, it is coming into maturity despite its fraught origins, using advanced approaches to dissect out confounders and identify direct genetic effects. One of the highest valence traits in the field and to society at-large is educational attainment and the related trait intelligence (IQ has been found to contribute to 43% of the variance in educational attainment).

Why Study the Genetic Contribution to Educational Attainment?

There are three potential benefits of studying the genetics of educational outcomes: (1) improving the quality and power of empirical research designs by controlling for genetic factors; (2) gaining biological insights that may lead to new drugs or theories for learning and memory or even neurodegeneration; and (3) identifying modifiable channels through which genes affect scholastic outcomes and enabling precision interventions.

Genes and Education

Studies of twins and adoptees in developed, Western countries have repeatedly shown that variation in genes plays an important role (roughly 40%) in explaining the differences in educational outcomes among people. This 40% figure for educational attainment is a measure referred to as “heritability.” Heritability is a statistical metric that describes the proportion of variation in a population accounted for by genetic factors. This can be further funneled down to identifiable causal effects as the figure below illustrates.

However, it is important not to get the wrong idea about heritability as there are some misconceptions about it. It does not indicate what proportion of a trait is directly caused by genes and what proportion is directly caused by the environment a priori. Rather, it indicates how much of the observed variation in a trait among individuals in a particular population at a particular time can be attributed to genetic variation. Heritability measures can and do shift over time. One of the most robustly replicated findings in behavioral genetics is that the heritability of cognitive skills rises gradually through childhood and adolescence. It isn’t a global or necessarily generalizable measure. It also doesn’t provide insight about which genes or environmental variables are involved with a trait or how they contribute to a given trait. With these caveats, heritability estimates still provide useful information about the impact of genetic variation. The figure below is a nice illustration of how twin studies that simply correlate trait similarity between twins, siblings, and adoptees can illuminate the influence of genetics on these trait outcomes (more genetically similar people have more similar outcomes).

Educational attainment as a measure that varies between individuals in a population can be subject to exactly the same experimental biological designs as other outcomes, for example, those studied in epidemiology and medical sciences, and the same caveats about interpretation and implication apply

~David Cesarini and Peter M. Visscher in npj Science of Learning (2017)

The GWAS Era

Only in the era of genomics (post-2000 but actually more like post-2010) have scientists been able to identify the DNA variants that causally influence educational outcomes. This is because the twin study designs, despite being powerful and compelling in many ways, rely on certain assumptions: the equal environments and genetic identity assumptions. Assumptions, despite being fundamental to any approach, can bias findings, and there are some possible confounders at play in twin studies. Here, enters the GWAS.

What is GWAS?

GWAS is a method to identify genetic variants that are associated with a trait or disease of interest across the whole genome. It involves collecting a large sample of individuals who have been genotyped for hundreds of thousands or millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and measuring the trait or disease of interest in those same individuals. Then, a statistical test for each SNP in run to compare the allele frequencies between different groups (case vs controls) or to correlate the SNP genotypes with the trait values. Correcting for multiple testing by applying a stringent significance threshold or controlling the false discovery rate is also an important step. The SNPs that pass the significance threshold are reported as genome-wide significant associations (often visualized in a Manhattan plot), which can be located near or within genes that influence the trait or disease of interest. Further functional validation and replication studies tend to be needed to confirm the causal role and biological mechanism of these SNPs. Additionally, other analyses can be performed to explore the genetic architecture of the trait or disease, such as estimating the heritability, calculating the genetic correlations, performing meta-analyses, fine-mapping the loci, and identifying gene-environment interactions. These analyses can provide more insights into the genetic and environmental factors that contribute to the trait or disease variation and causation.

Direct Genetic Effects, SNP-Based Heritability, and Polygenic Scores

The use of highly powered (i.e. large samples) within-family GWAS designs allows for the estimate of direct genetic effects. Direct genetic effects (DGE) are the effects of an individual’s own genotypes on a given phenotype, i.e. the specific set of SNPs passed from parents to offspring that influences the trait in question. This is an exciting time because we can now reliably detect specific SNPs associated with various behavioral traits and begin the challenging work of elucidating why these associations exist and how these genetic variants may contribute to behavioral outcomes. The complicated part is that these SNPs tend to have tiny effects, which means massive samples sizes are required. The effects tend to be generalized as well (e.g. pleiotropy), making elucidating the biology at play a challenge. There are also other important confounding factors like population stratification and assortative mating that have to be adjusted for as well. Regardless of these limitations, there has been great progress. Plus, we may eventually be able to use these findings to build polygenic index (PGI) measures that may reliably predict social outcomes. The figure below shows various attempts to measure the genetic effects of SNPs on educational attainment.

Genetic Prediction and Individualized Educational Plans Informed by Genetics?

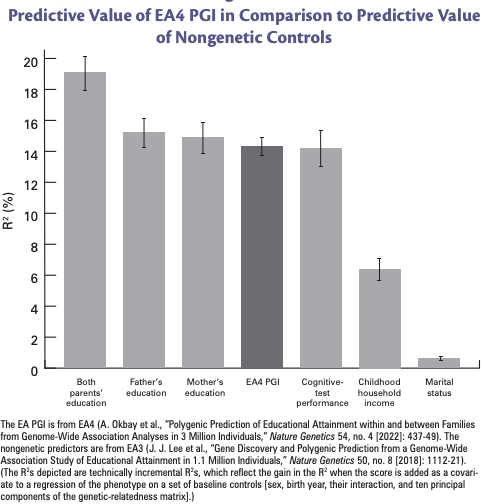

As our genetic knowledge grows in the modern genomics era, the improved PGIs may allow for reliable prediction of educational outcomes. This wouldn’t be just for years of education alone, but for other traits related to educational performance and achievement, including both cognitive and non-cognitive traits. The closer we get the measurement of traits to biology and understand how that biology influences social outcomes, the more powerful the genetic data will become. The amazing thing is that the PGI for educational attainment already outperforms or performs similarly with traditional social science variables (see figure below).

Beyond insight into the biology of the brain, the predictive power of behavioral genetic studies alone may justify the use of these designs. This isn’t to say we should be using the EA PGI to track individuals today, but we should accelerate this work so that we can evaluate whether such an approach may be helpful. Education today is a struggle for many and isn’t necessarily optimizing everyones skills and capacities. Freddie deBoer has written about this in his book The Cult of Smart and behavioral genetics Kathryn Paige Harden addresses similar themes in her book The Genetic Lottery. Beyond educational tracking, these approaches may be especially adept at identifying at-risk individuals who require more intensive instruction and intervention. The figure below shows the expected predictive power of PGI given certain sample sizes.

However, it is important to be cautious about how much predictive power can be achieved with complex traits from the GWAS approach alone, even with very large discovery samples of millions of people. For instance, for height, which is highly influenced by genes, the above figure shows that the predictive power of a PGI may soon be comparable to, for example, the predictive power from the average height of one’s biological parents. But I think we should remain optimistic as the height PGI as progress has been rapid. Just last year (the above figure is from 2017), a new study demonstrated that the PGI for height can explain within-family variation better than average of parental heights. The study also found all of the “missing heritability” for height (study here). Beyond very biological traits like height, genomic predictions will be feasible for various learning outcomes and neurodevelopmental disorders. PGIs may also be useful in research on how skills develop over the life cycle, as shown by a 2016 study with very rich phenotypic data collected from individuals followed for up to 40 years. The study found that PGIs were positively related to reading and speaking skills in early childhood, later academic achievement, and an index of economic security in adulthood. A mediation analysis revealed that about half of the effect of the PGS on the adult outcomes was mediated by measured cognitive and non-cognitive skills. Children with higher PGIs were more likely to grow up in households with higher socioeconomic status and perhaps most interestingly, the PGI predicted the likelihood that a child from a lower socioeconomic status household would move up the social ladder. In some cases, knowing one’s genetic risk may help parents choose better environments for their children (although this knowledge is not very helpful if there is no environmental intervention available to reduce or compensate for the risk).

At this moment in time, there are few practical or policy implications to takeaway from this research, other than the nature and nurture processes that contribute to traits are bound up tightly together, often correlated directionally, and that genes are an important part of the overall equation. However, I think we should expect and hope for more precise interventions that can be arrived at due to great behavioral genetic research. This type of research will identify both innate and non-innate variables that we may want to tweak optimize everyone’s potential. There is concern this type of research will promote fatalistic ideologies - things are the way they are because of unmodifiable factors and so on. Although I do thing there is quite a bit of inertia related to social outcomes, I don’t think a deeper understanding of how genes and environments affect outcomes will promote fatalism. If anything, it will illuminate some of the levers we can pull to make a difference and may help us match natural proclivities and talent with resources and opportunities.